3. Perspectives on trust

As noted at the outset of this article, Satoshi identifies trust as the major issue, as evidenced by the following quote:

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work.

But what kind of trust was Satoshi referring to in his criticism of conventional currency? On the basis of all of his published statements and comments, one can infer that he was referring to ‘blind trust’ (i.e. blind faith) in the majority of instances.

A system in which compliance with the rules of all system operations is easily verifiable is always superior to a system based on blind trust. At least when the outcome is essential and matters more than the relationship, as is the case with a money system. This is why we must be able to verify the correctness of all operations in a money system.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible for the average person to obtain deep insights into the internal operations of banks and financial institutions, let alone influence them, which is why these systems demand a high level of blind trust from their users.

But if blind trust is required to make a money system work, then trust in the operators becomes a dependency. And according to Nick Szabo personal property has not and should not depend on trusted third parties, because they are security holes. Therefore, if a system depends on blind trust to function, it has a dependency on security holes. And since security holes pose risks to the system’s users, such a system is inherently dangerous. This obviously discourages users from utilising such a system.

Instead, we require a money system that is widely trusted (and therefore utilised) by as many people as possible. To accomplish this, a money system must minimise the risk for users, which necessitates as few security holes as possible, which in turn requires a minimal dependence on blind trust in the system.

So, what we actually want is blind trust dependency minimisation rather than trust minimisation.

This leads us to assume that every time Satoshi spoke critically about trust, he was criticising the dependence on blind trust.

Here are two examples to illustrate this point:

- When someone says: “Trust me please”, and you have no option but to comply, then this is a dependence on blind trust.

- On the other hand, when someone says: “Don’t take my word for it, see for yourself” and provides all the evidence required, then you’re not required to trust them blindly, which builds trust (as long as the evidence matches their words).

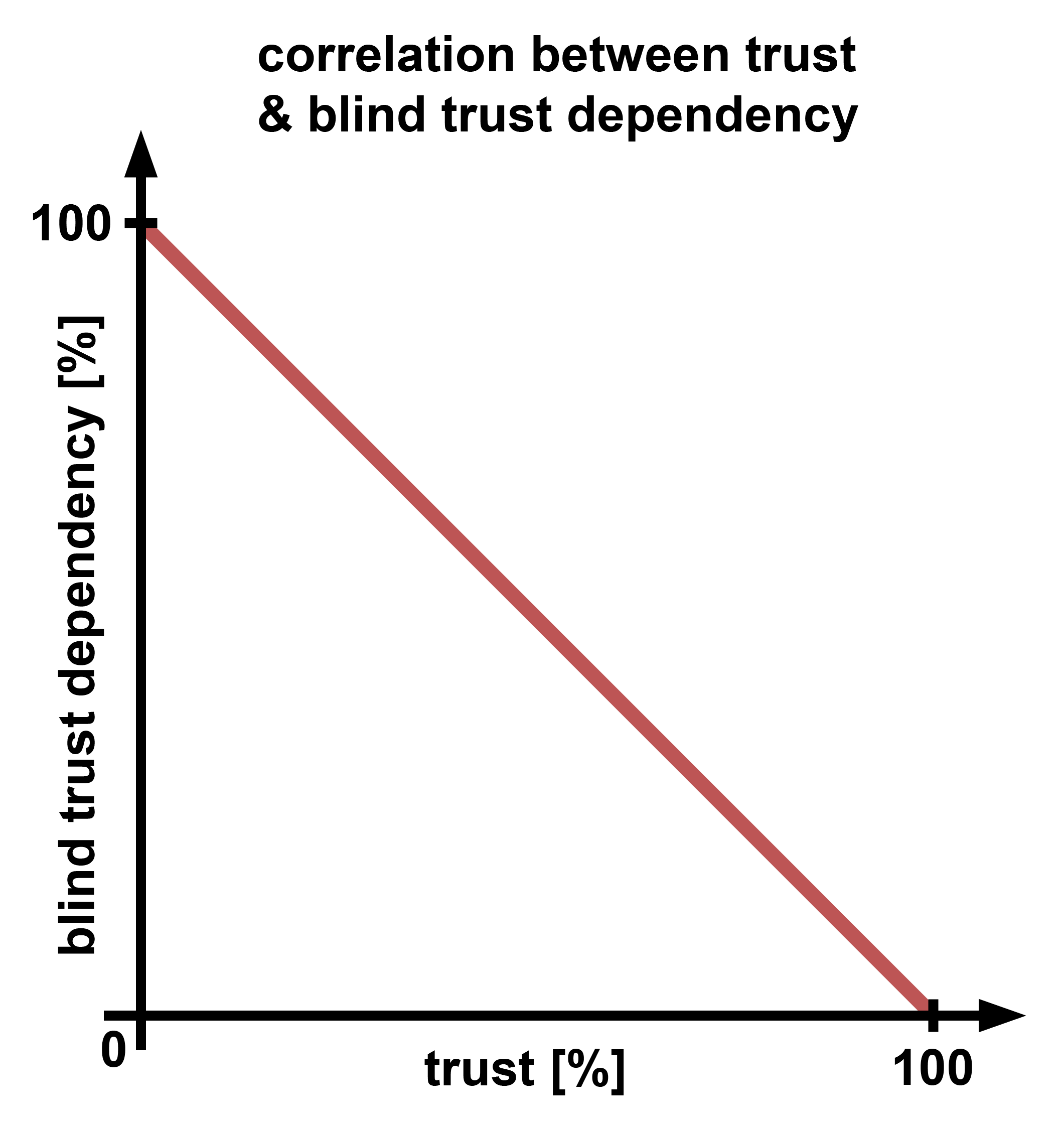

Moving forward, it is important to differentiate between ‘trust’ and ‘blind trust dependency’, because they are negatively correlated to each other. The lower the dependency on blind trust the higher the trust in that system, and vice versa.

In other words, every social system (especially money systems) relies on the trust of its users. Whether it be blind trust, or trust based on the users’ ability of verification of, and participation in the operation of the system. The total amount of trust in any social system is always a combination of these two components (i.e. the sum of the two values of both axes of the graph shown above, so to speak).

In summary, these are the two perspectives on trust:

Good trust:

Voluntary trust is a positive quality in and of itself! It makes users feel safer, attracting more users as a result.Bad trust:

Dependence on blind trust is bad! It increases the security risk for users, thereby discouraging their use of such a system.

So, the question is now: how to replace blind trust dependency with user-generated trust? To determine this, we must identify the elements that inspire user confidence in a DLT system.