Abstract

The fiat monetary system is broken and the world desperately needs a proper solution to replace it. But to take on the established monetary and financial systems, a decentralised technology cannot afford any weaknesses, as this would slow down or even prevent rapid global adoption. An ultimate solution is therefore needed.

We believe that such a solution is achievable.

This solution is a decentralised technology without any of the problems blockchain-based systems face today. It will be more secure, more decentralised, more scalable, faster, cheaper, fairer, more energy efficient, more user-friendly, and will have better privacy and more features than any current decentralised technology. This new technology can deliver on all of these promises without compromise.

Sounds like a scam to you?

We share this concern! That is why we have written an in-depth article that takes you on a journey in search of a future-proof money system. It will take you from the invention of Bitcoin (the first working decentralised technology capable of holding value), to the underlying problem Satoshi (Bitcoin’s founder) set out to solve, to the first principles of trust and money, and finally to a completely new approach that is able to achieve a combination of characteristics and features that has always been considered impossible.

We believe this new technology will herald an unprecedented revolution of a decentralised future, far exceeding the adoption of any other decentralised technology to date.

Part 1: The Problem

Please read this first!

If you want a better grasp of how our current monetary system works, or if you want to learn more about Bitcoin and blockchain, please refer to the Resources section at the end of this article for a plethora of reputable information.

If you wish to check the (almost 800) sources we have linked to in this article, we strongly suggest you read this article on a desktop computer using a Chromium-based browser (such as Chrome, Edge, Opera, etc.) as we have made extensive use of Chromium’s link to quotes & text feature. By the way: Blue links are links that have not yet been visited. They turn purple when the page behind them is visited.

We do not know if Satoshi is a man, a woman or a group of people. But since Satoshi is a male name and for the sake of readability, we will refer to him as a male person.

The research of this article took about a year and we are aware that it is impossible for anybody to become an expert in multiple complex subjects within this short amount of time. Therefore please bear with us if you spot a mistake or other inconsistencies in the article, and let us know in the comments below so we can correct, improve or clarify them.

Satoshi Nakamoto is a genius.

Although he was not the first to attempt to create a decentralised digital money system, his conception was the first that achieved the breakthrough. In addition to its first-mover advantage, Bitcoin’s overwhelming success and ongoing financial supremacy over competing cryptocurrencies (also known as altcoins) can be attributed to this technology’s incredibly sophisticated and well-designed architecture.

Not only did Satoshi address a multitude of technological obstacles (including the problem of double-spending). But more importantly, he endeavoured to address one of the most pressing problems confronting the world today: the escalating instabilities associated with our current fiat-based financial system. This was undeniably the primary reason behind his creation of Bitcoin.

But does Bitcoin offer the ultimate solution?

To determine this, we must first have a deeper comprehension of the underlying causes of the problem Satoshi wanted to solve. Examining Satoshi’s initial public announcement of Bitcoin, the basis of the problem as he perceived it is readily apparent.

You are encouraged to read the entire announcement, but for the sake of brevity, we will just discuss the areas that are pertinent to our discussion.

Let’s begin by analysing his second paragraph:

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts. Their massive overhead costs make micropayments impossible.

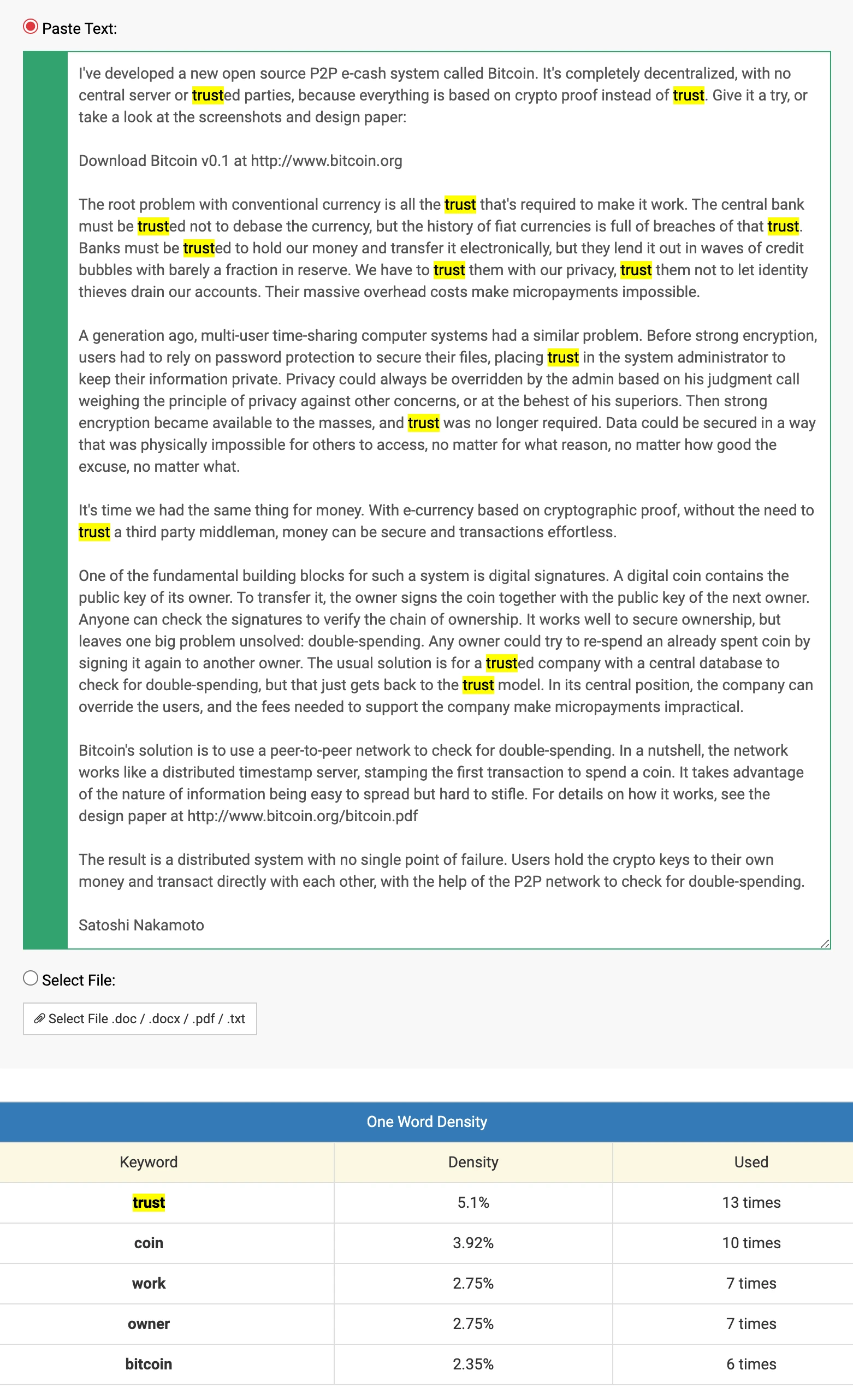

The issue that Satoshi clearly wants to call our attention to is demonstrated by his repeated use of one word: Trust.

The above paragraph contains six occurrences of the word ‘trust’. And if we analyse his full announcement, we find that the word trust appears a total of 13 times, making it the most commonly referenced keyword in the whole text.

It seems quite evident at this point that there is one thing that fundamentally concerned Satoshi with regard to fiat currencies as well as our current financial system and institutions: Trust.

The Battle Against Trust

Satoshi’s solution

Referring back to Satoshi’s initial public announcement of Bitcoin, the following three statements stand out:

It’s completely decentralized, with no central server or trusted parties, because everything is based on crypto proof instead of trust.

Then strong encryption became available to the masses, and trust was no longer required.

With e-currency based on cryptographic proof, without the need to trust a third party middleman, money can be secure and transactions effortless.

In each of these statements, Satoshi expresses his belief that cryptography can replace trust.

In the Bitcoin Forum, he wrote:

At some point I became convinced there was a way to do this without any trust required at all and couldn’t resist to keep thinking about it.

Again, Satoshi asserts that at a certain point he became confident there is a solution that does not involve any trust at all.

However, is this actually feasible? Can the need for trust in a money system be eliminated entirely?

What is a trustless money system?

The terms ‘money’, ‘currency’, ‘money system’ and ‘monetary system’ all appear frequently in this article. Understanding their respective definitions is crucial, as they are not interchangeable.

Even though Satoshi never mentioned the now commonly used term ‘trustless’, it accurately captures what he meant in his words cited in the previous section.

Therefore, what characteristics must a money system possess to be termed trustless? The widespread opinion since the launch of Bitcoin says that there are two essential components of a trustless money system:

No central authority holding influence over the money supply or ownership For a money system to be considered trustless, there must be no central authority with influence over either (i) the money supply or (ii) individuals’ holdings.

- A central authority holding influence over the money supply can devalue the money by (excessively) increasing the money supply. This causes inflation (also known as arbitrary confiscation, hidden tax or taxation without representation) which disproportionately affects the working class and those on low incomes.

- A central authority holding influence over the ownership of money (individuals’ holdings) has the power to freeze bank accounts; seize funds from bank accounts; halt transactions to unauthorised payees; and so on.

Peer-to-peer transactions without a third-party middleman Transactions in which a direct exchange occurs between a seller and a buyer without the need for one or more trusted intermediaries (or third-party middlemen).

As soon as one or more third parties are required to facilitate a money transfer, trust is automatically implicated, as both sides become dependent on these third parties for the transaction to occur successfully.

So, as Satoshi points out in his initial announcement of Bitcoin, a fiat currency can never be a trustless money system as a central authority has sole influence and power over the issuance of its currency:

The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.

Thus, a trustless money system is a system that does not have a central authority, nor does it require third-party intermediaries to facilitate transactions, yet still serves all three functions of money:

A good illustration of this would be gold.

Gold as an example of trustless money

Gold is the ideal example of trustless money due to the fact that it performs all the functions of money, yet no central authority can manage its supply or ownership, and no middlemen are required for transactions.

The following characteristics demonstrate why gold holds value and can be used as money:

- difficult to mine (gold can not be printed or electronically created like fiat currencies)

- scarce (the amount of gold in circulation increases quite slowly)

- non-replicable (impossible to duplicate)

- unforgeable (there is no cheap way to synthesise a material with exactly the same properties and characteristics as gold)

- durable (it is the most corrosion and oxidation resistant metal available)

- divisible (can be broken into smaller amounts without losing value)

- fungible (every piece of gold has the same chemical structure, properties and characteristics as any other piece of gold - apart from shape and weight)

- dense (high value to weight ratio)

- liquid [of assets] (can be easily converted to other means of payment)

- distributed (ownership and transactions do not require a central authority or third-party intermediaries)

- anonymous (privacy of the owner and confidentiality of transaction details)

However, gold has one major disadvantage in today’s digital age: Gold is tangible.

This one characteristic entails numerous drawbacks that renders gold very impractical as a means of payment:

- It is difficult to safely store large quantities of gold, which is why most owners keep it in bank vaults. However, this in itself carries the risk of confiscation, as occurred in 1933 under Executive Order 6102.

- Gold is difficult to identify for non-specialists. This means a seller cannot instantly verify the legitimacy of the gold received from a buyer.

- Even though gold is divisible, it is not possible to swiftly and simply separate the correct quantity from one’s gold holdings for each transaction.

- Typically, one only carries a limited quantity of gold in order to minimise the risk of loss and/or theft. This could lead to complications, for example, if the amount carried is insufficient for an unexpected expense.

- To exchange goods and services for gold, the buyer and seller must be physically present in the same location. Consequently, long-distance transactions are not possible, unless you use a middleman making the transaction incredibly costly and time-consuming. A middleman would also remove anonymity and ‘trustlessness’ from the transaction.

Digital money does not suffer from these problems. Quite the contrary. Digital money is:

- easy to store (one can hold any amount of funds in self-custody without the risk of confiscation)

- easy to identify (the capacity for all users to verify the authenticity of a transaction)

- easy to divide (the ability to pay exactly the right amount each time)

- easy to transport (access to one’s entire funds from anywhere and at any time)

- easy to transact remotely (the ability for cheap, fast and easy transactions over long distances)

Therefore, it is evident that the world will certainly never return to using shiny yellow rocks as their primary means of payment. Our digital world demands digital money.

What about digital gold?

Given the attractive characteristics of gold as money, and the need for money to be digital, it follows that the ideal money system would be some form of digital gold.

Unfortunately, the following two characteristics of gold are mutually exclusive to digital money:

- non-replicable (impossible to duplicate)

- distributed (ownership and transactions do not require a central authority or third-party intermediaries)

Never can digital money be both non-replicable and fully distributed at the same time (like gold). This is because a means of payment is only considered to be fully distributed when it is possible to both own and transact it without the need or permission of one or more central authorities, organisations or any other intermediaries. Thus, if no trusted third party is needed, the information about possession or any transactions performed need not be recorded anywhere and is known only to the owner or the transacting parties.

Within the context of gold:

- Gold can be purchased without any special authorisation.

- In the vast majority of instances, one is not required to identify oneself when purchasing gold, and you will not be entered into any database.

- When one trades gold for products or services, the transaction is solely between the buyer and seller (peer-to-peer).

- No trusted third party is required for the transaction as the seller can independently verify the gold’s authenticity.

- A seller can be confident that gold will retain its value over an extended period of time (i.e. that he can exchange it for other goods and services of comparable value at a future date).

- Information such as sender, recipient, amount, time of transaction, etc. do not need to be reported or stored anywhere.

Therefore gold is a perfect example of a fully distributed money system. However, this is impossible to achieve with digital money, as it would allow the money to be duplicated.

But why is fully distributed digital money replicable?

Because the digital representation of value is just information, consisting solely of ones and zeros on a digital storage medium. As a result, a fully distributed digital money would be easy to replicate (similar to copy and paste on computers), unlike a chemical element such as gold, which is uneconomical to produce synthetically.

This problem is also known as the double-spending problem, because money that can be easily multiplied can also be spent several times.

If you want to know more about the double-spending problem and why it is impossible to simply use ordinary digital files as money that can be sent to someone else by email or text message, we recommend you read this very easy-to-understand article: What Problems Did Bitcoin Solve?

This forms the basis as to why it is theoretically and practically impossible to create a true digital gold equivalent.

Why digital money can never be trustless

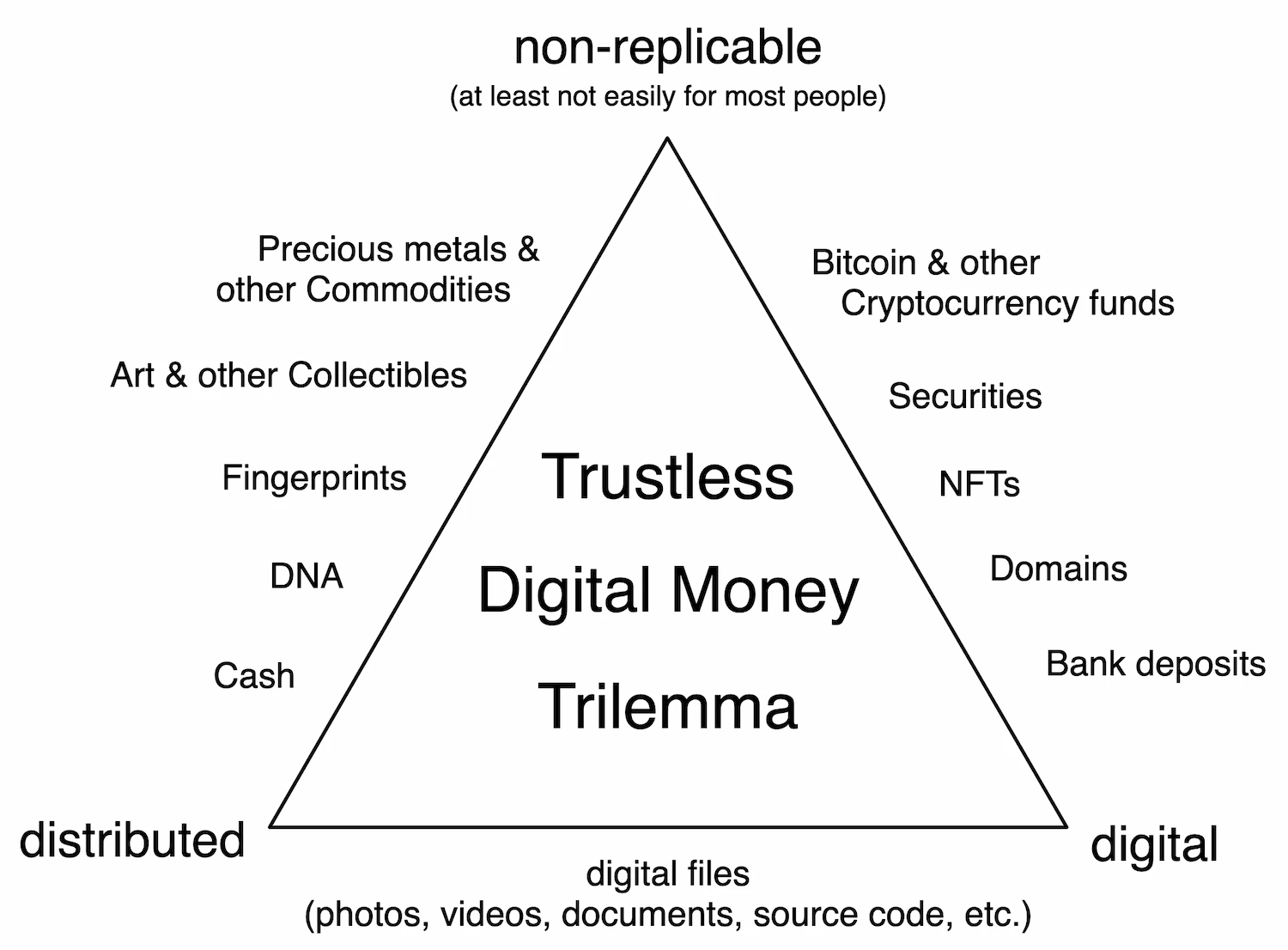

If it is impossible to create a true digital gold equivalent, this presents us with the following challenge, which we call the Trustless Digital Money Trilemma:

Ultimately, this means that if you want to create a trustless digital money (digital money with the same attractive properties as gold, apart from being tangible), you would have to be able to own it without the information about ownership needing to be stored anywhere other than on the respective owner’s device(s) (i.e. without the need for a ledger). In the figure above, however, it is striking that all of the examples listed, which are digital and non-replicable, use some kind of centralised or decentralised ledger to keep records of holdings and transactions (such as a blockchain in the case of Bitcoin).

The reason all digital representations of value must store records somewhere shows us that something of value is only valuable as long as it is not easily replicable. In other words, if you have to choose between ‘non-replicable’ and ‘distributed’ as a property of digital money, the obvious choice would have to be non-replicable since money that can be replicated holds no value. However, this implies that we must abandon the distributed property. And this in turn means that if the holdings and transactions have to be stored and processed by trusted third parties, a digital money system can not be considered trustless.

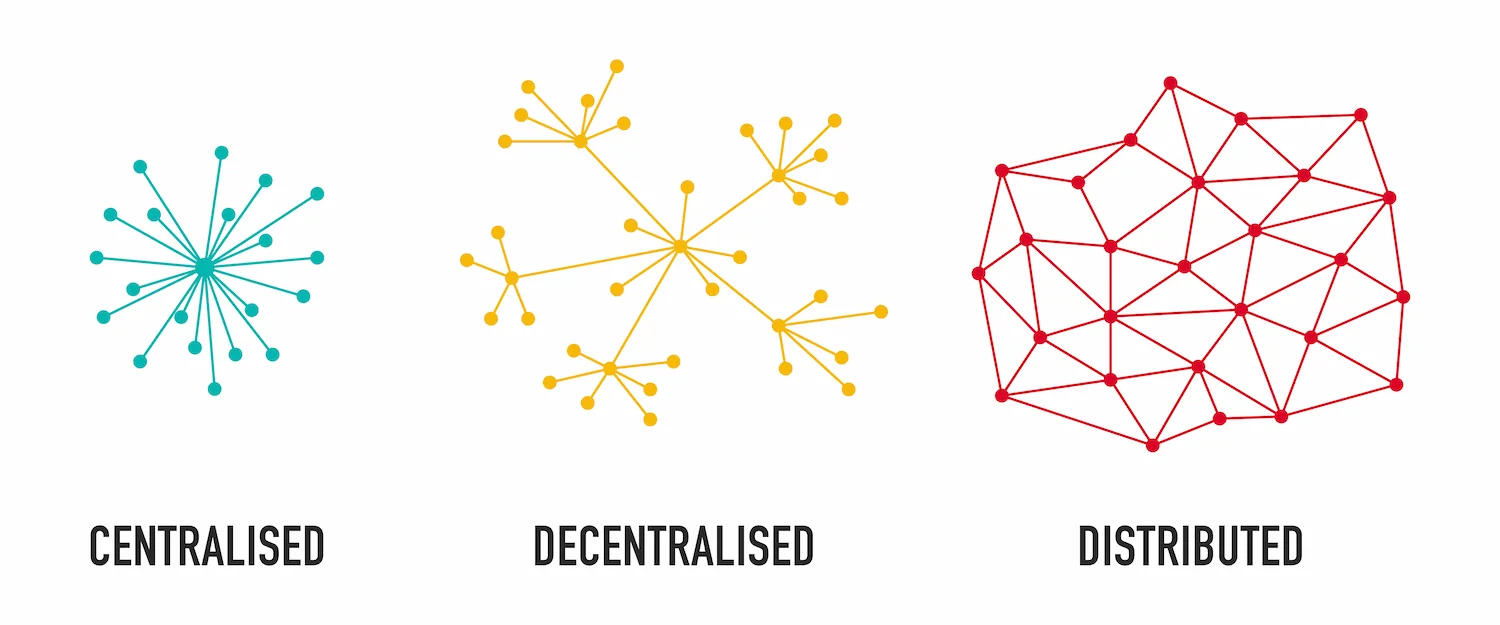

So, if a distributed digital money system is technically impossible, we are only left with decentralised or centralised alternatives. Technically speaking, a centralised system would be much more efficient and easier to implement than a decentralised system; therefore, we should first consider whether a decentralised system is even necessary? Decentralisation would in fact be unnecessary if a single central authority could solve the trust issue.

Unfortunately, there has never been a single authority (person, organisation, government, etc.) in the entire history of humanity that enjoyed the complete trust of all individuals, regardless of how much good they have done in the past or how honourable their intentions may have been. Everybody has critics, including the most widely admired people of the 20th century. Especially bankers, politicians, and government ministers, who wield the most authority over our monetary systems are actually one of the least trusted professions according to a survey conducted by IPSOS in 2019.

Even if there were a single authority that enjoyed the complete trust of all people, there would still be no guarantee that this authority would remain true to its high standards and exemplary conduct, creating a single point of failure. For this reason, a centralised system is unsatisfactory.

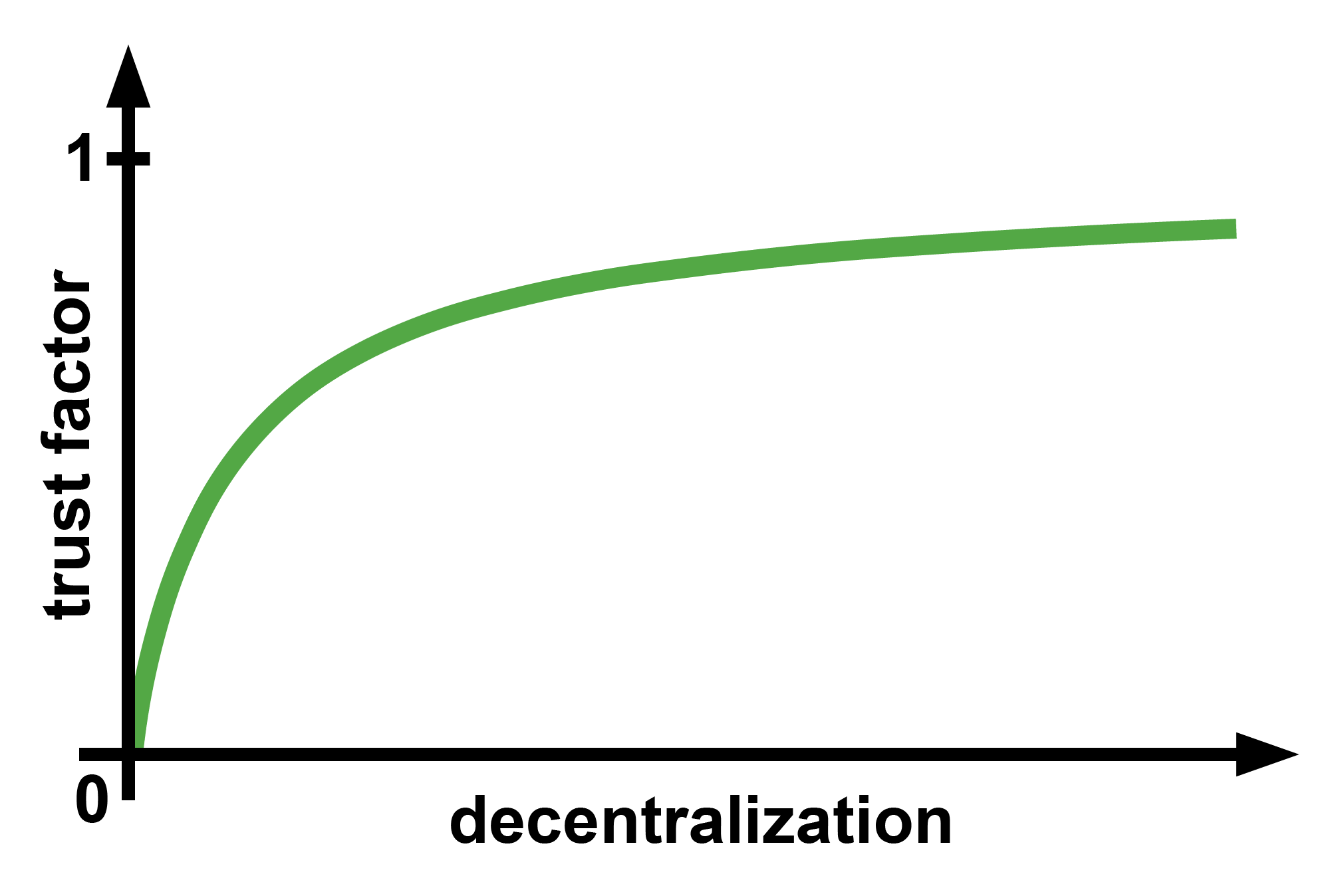

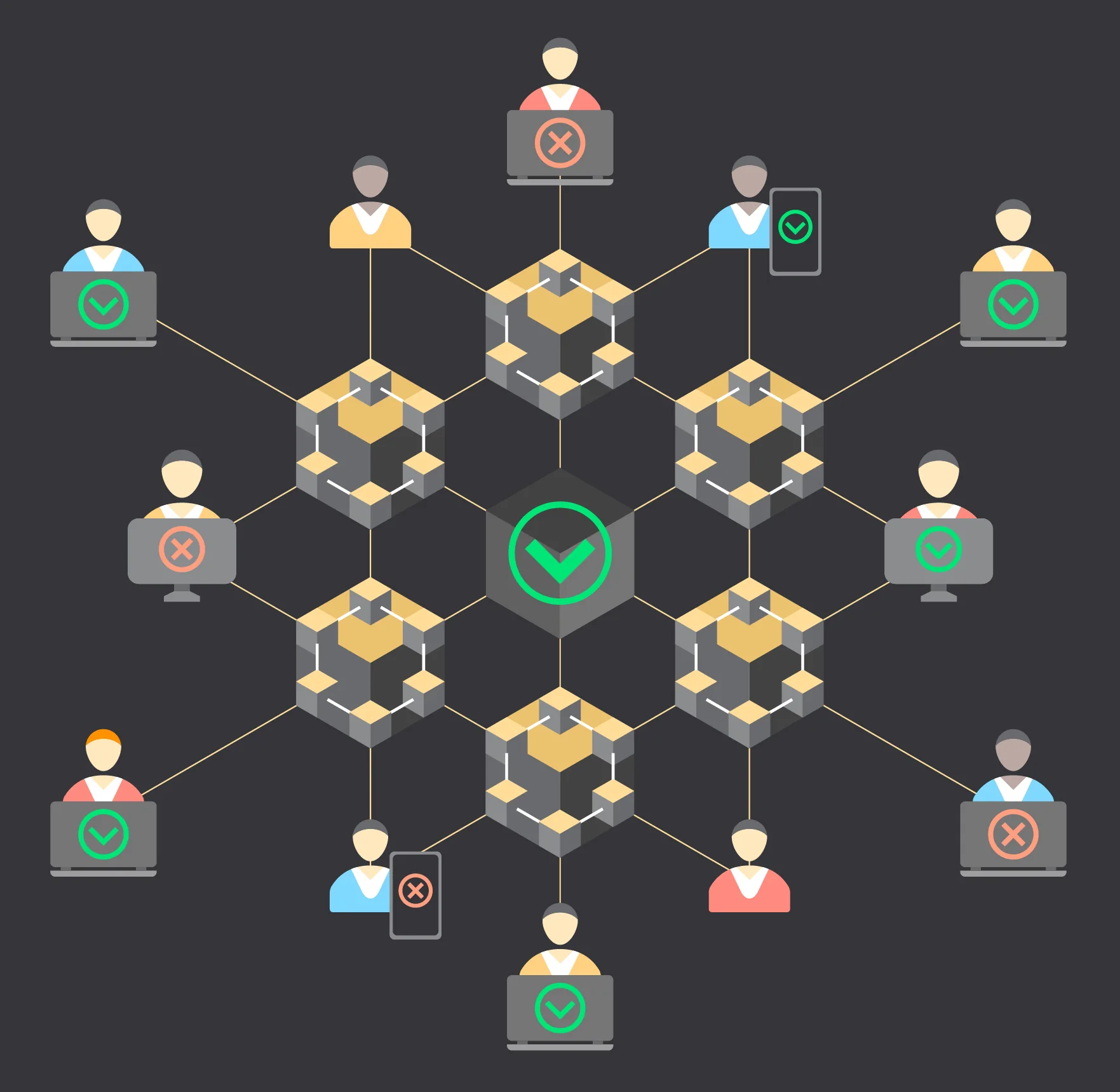

To minimise the risk of a breach of trust, the only option left is a decentralised system. Spreading the responsibility for the integrity of a system across many different operators is clearly beneficial to its trustworthiness.

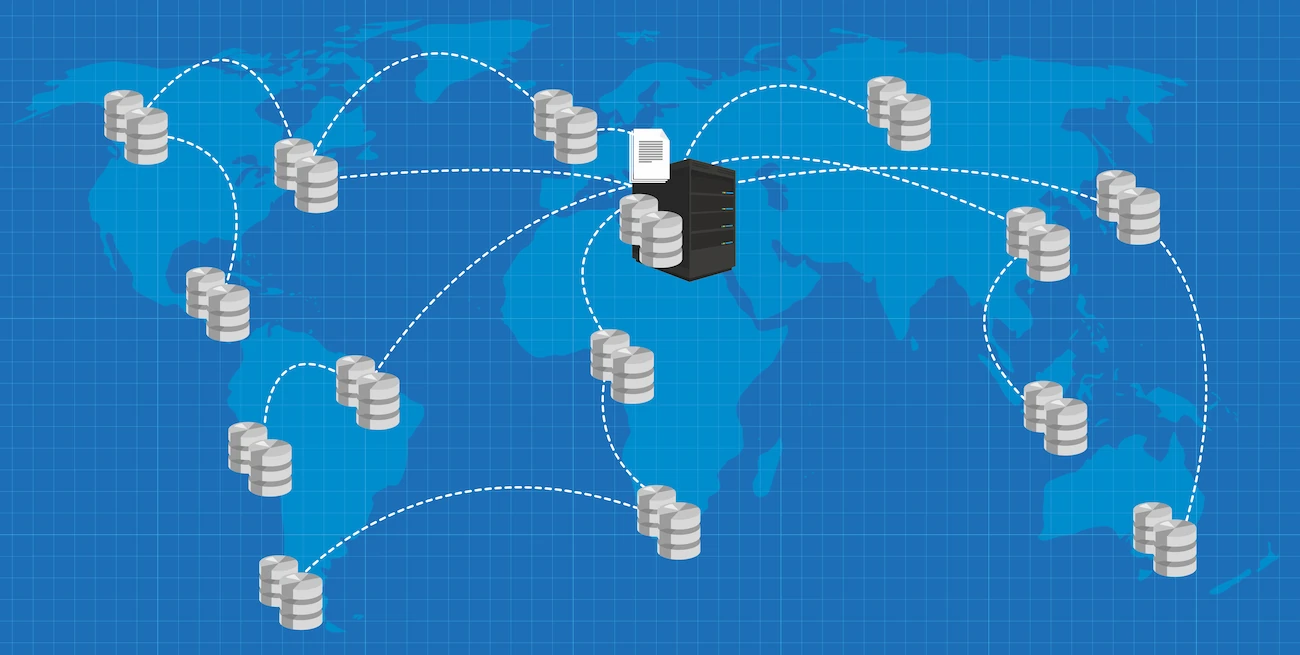

We argued that a digital money system can never be fully distributed (like gold), but rather needs a ledger that is operated by a decentralised network of trusted third parties. Therefore, we believe that the term Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), which is commonly used to describe blockchain-based solutions and the like, is not entirely accurate. Instead, a better term might be: Decentralised Ledger Technology (which means we can continue to use the abbreviation DLT).

This ultimately means that any digital money system cannot avoid intermediaries who must be responsible for storing the ledger and processing transactions. Nonetheless, we are able to avoid centralisation by involving a large number of intermediaries. By doing so, such a system is neither considered distributed nor centralised, but becomes a decentralised system.

The one thing Satoshi didn’t get right

Subsequently, if intermediaries are still needed to store the ledger and process transactions, users must continue to trust middlemen, even in a decentralised money system.

After all, network operators are also potentially fallible human beings. Imagine a decentralised money system run exclusively by the same individuals that run the fiat monetary system? What difference would it make as to whether users must place their trust in the bankers or in the network operators?

Yes, it is true that in a decentralised money system trust in the individual operators of the system is minimised (inversely proportional to the share of operators), but this doesn’t change the fact that a decentralised money system cannot render this trust superfluous, or eliminate it altogether. In fact, in recent years, it has become abundantly clear that untrustworthy operators holding a significant influence over a cryptocurrency has almost without exception led to its demise.

The same applies to Bitcoin. Satoshi himself stated in his white paper release email back in 2008:

As long as honest nodes control the most CPU power on the network, they can generate the longest chain and outpace any attackers.

Therefore, a condition exists: The nodes that control the most CPU power in the network must be trustworthy.

The certainty that one’s money is safe stems from the fact that one has faith in the miners with the most CPU power (as well as the majority of node-operators). They must be considered trustworthy miners (and node operators).

We are not claiming that any traditional banking system is equally or more reliable than a decentralised money system such as Bitcoin. Quite the opposite! Bitcoin possesses a number of characteristics that make it a very trustworthy system. However, as previously identified, it is theoretically impossible to create a money system in which users do not have to trust any individual or group of individuals.

Consequently, blockchain technology does not eliminate trust. It simply transfers it to other parties. A person who favours a blockchain-based money system over a fiat currency is essentially stating, “I trust the miners, node owners, blockchain developers, wallet developers, cryptologists, (and if funds are stored on an exchange also the exchange owners and their employees), as well as my own technical abilities (e.g. not to lose my private keys) more than I trust central bankers, influential politicians, commercial bank owners, directors, fund managers, risk managers, etc.”.

Even if someone is a software developer and cyber security expert who has read the source code of the most used blockchain node implementations and the wallets he uses and determined that there are no bugs or backdoors, he must still trust the miners and node owners.

Thus, we have discovered that even in a decentralised system, we must still rely on intermediaries.

There is no “way to do this without any trust required at all”.

Trust cannot be eliminated.

This is what Satoshi didn’t get right.

What about blockchain, cryptography, decentralisation…?

Subsequently, even if a trustless state is not achievable with digital money systems, it appears that ‘trust minimisation’ is at the heart of many cryptocurrencies (at least to a certain degree).

However, it is essential to comprehend the rationale behind this. In reality, this is not because blockchains or cryptography are trust-minimising technologies, but rather because (1) all transactions and processes in the system are 100% transparent, (2) the responsibility for the operation of the system is distributed among many parties, (3) these parties are liable for fraudulent behaviour, and (4) anyone can use the system without revealing their identity.

Transparency:

In a DLT system, transparency means that the rules of the game are clearly defined and accessible to all; that compliance with these rules is easily verifiable by all; that the source code is publicly available; and (for most cryptocurrencies) that all transactions, including the entire transaction history are publicly visible. Obviously this results in maximum transparency and transparency is the key to building trust. (Needless to say, user confidentiality is not part of this transparency. Bitcoin, for instance, is ‘pseudonymous’, meaning the identities behind transactions are not stored on the blockchain.Decentralisation:

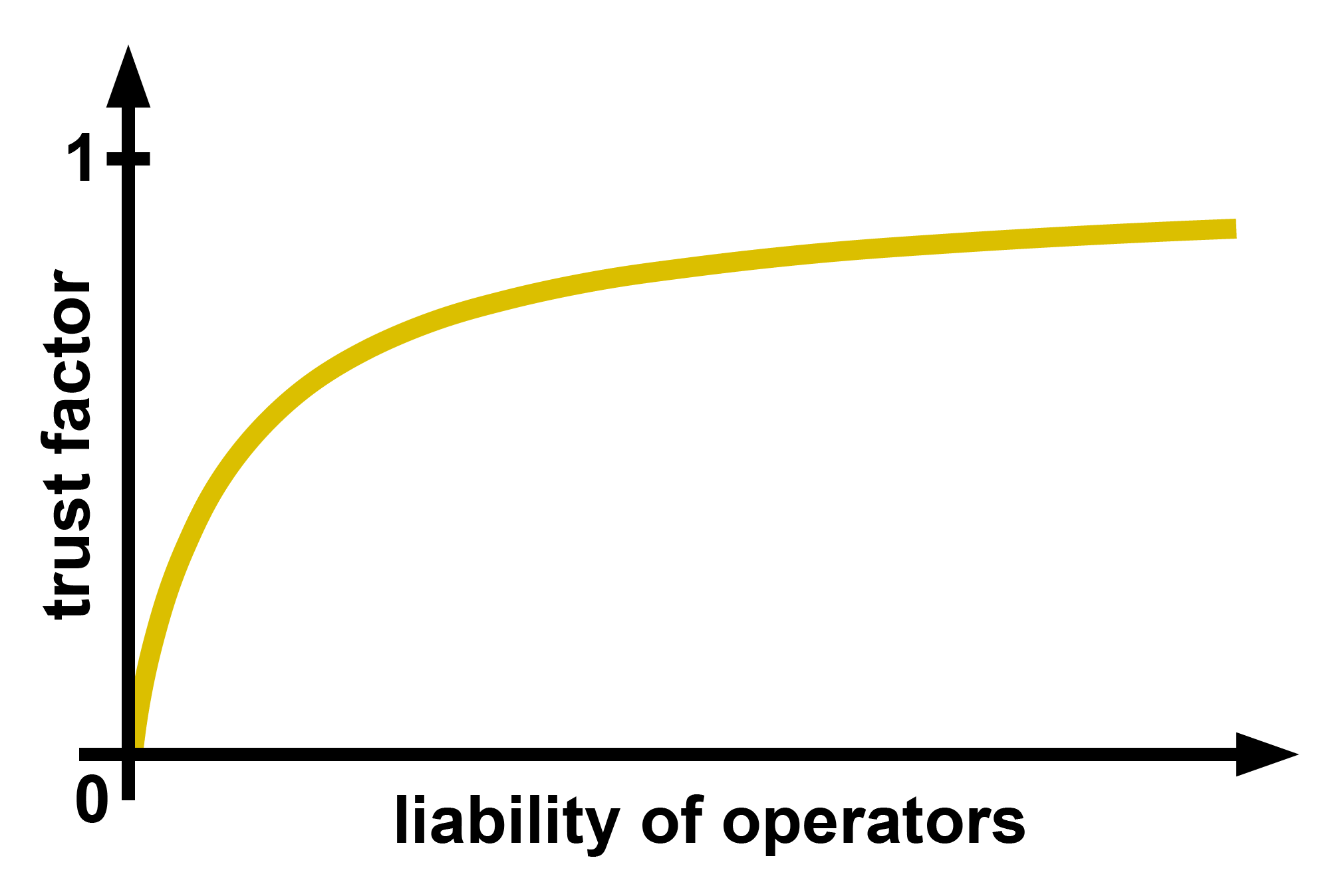

When a system is controlled by a single authority, all the trust required (to make that system work) is demanded by that authority. As history has shown us, this authority has complete freedom of action and is highly likely to exploit this position of power at some point. As soon as a second party with equal rights joins the system, the likelihood of untrustworthy behaviour decreases dramatically, as coordination between these two parties then becomes necessary. If there is secret collaboration between several parties to the detriment of others, this is known as a conspiracy. The more operators with equal rights join this system, the more difficult and therefore improbable a conspiracy becomes. This means that as the number of operators in a system increases, the required level of trust in each participant decreases logarithmically.Liability of operators:

In every social system, whether it be a state, a school, a family, a club, etc., there must be rules that allow people to coexist peacefully. However, these rules only make sense if there are consequences for violating them. And depending on the consequences of undesirable behaviour, people in this system adhere to the rules more or less strictly. This implies that the real question shouldn’t be about the severity of consequences, but rather which consequences are chosen to achieve rule-abiding behaviour. However, just as with child rearing, opinions regarding the effectiveness of consequences vary greatly. But one thing is certain: If members of a social system did not fear any consequences for undesirable behaviour, this would not only result in chaos, but it would also encourage certain individuals to seize power within the system (or at least try to). And once they have gained power, they would use that power to game the system for their own benefit. Consequently, every social system requires rules. In the case of Bitcoin, the consequences for not following the rules are that all the work that was done with electrical power is discarded, resulting in a financial loss.Privacy:

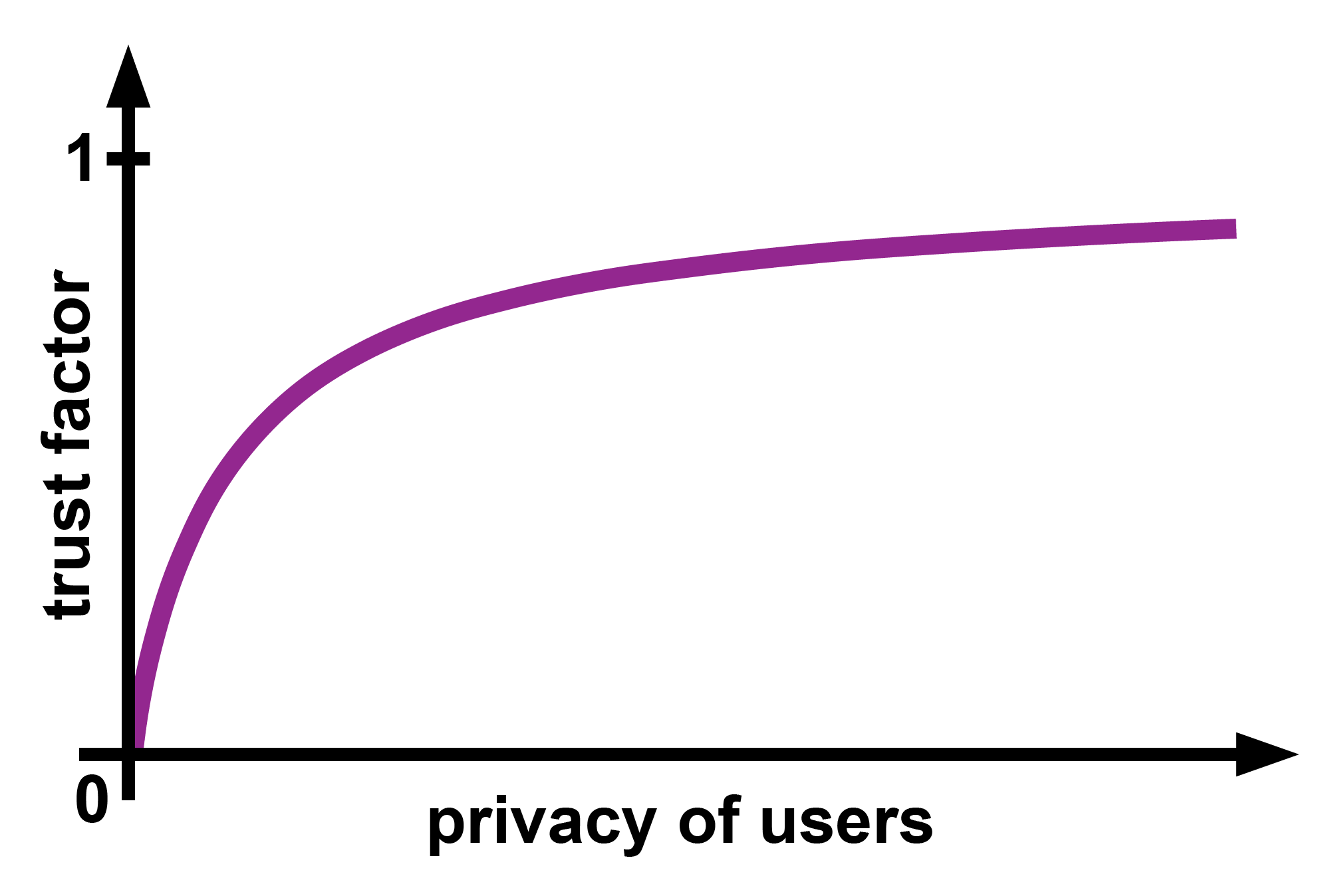

First, it should be noted that privacy and confidentiality are not interchangeable terms. Even though all Bitcoin transactions are visible to the public, Bitcoin’s protocol does not store (and thus can’t reveal) the identities of those involved. Above all else, it is crucial to recognise that privacy is a basic human right that is an essential component of greater freedom. The term ‘privacy’ encompasses a variety of facets, including financial privacy. However, anyone who wishes to open a bank account is required to provide identification, so all financial transactions can always be attributed to a specific identity. This means that bank employees can always see how much money you earn, how much you own, and what you spend your money on. Besides, credit card companies can create a tracking profile for each individual based on the information about when, where, and what they purchased. Obviously, government interference in people’s bank accounts, such as freezing or even confiscating funds, is far more severe. And this is precisely why privacy helps to build trust.

Therefore, the combination of transparency, decentralisation, liability of operators, and privacy protection of users in blockchain-based systems ensures that users are more likely to trust such a system than a system where:

- All decisions are made by a small group of people;

- one has little or no insight into, or influence over its processes;

- the operators of the system are not liable for their actions and don’t have to fear any consequences even in case of exploitative behaviour;

- all transactions of all users can be thoroughly screened by the operators; and

- decisions are routinely made to the operators’ advantage and to the users’ detriment.

It is thus the characteristics of a decentralised money system like Bitcoin why many individuals view it as more trustworthy than the alternatives (especially the fiat monetary system). For example, decentralisation enables users to have less faith in individual operators, however, it simply distributes rather than eliminates the need for trust.

It is essential to understand that regardless of a system’s trustworthiness, the overall level of trust a user must have in a money system is always the same independent of the money system. Simply put, it’s just easier for a user to place all the required trust into a trustworthy system rather than an untrustworthy system.

So, is blockchain, cryptography, and decentralisation the answer to the trust issue? Not alone.

Is blockchain, cryptography or decentralisation necessary to solve it? Yes it is.

Consequently, if the combination of blockchain, cryptography, and decentralisation is only a portion of the solution, then something else must be required to provide a working solution.

In order to unravel what this needs to be, we first have to agree on certain terminology surrounding trust, as trust seems to be a very blurry term among DLT enthusiasts and is used differently by a lot of people in this space. Since clarity is the key, let’s unblur it in the next sections.

First Principles of Trust and Money

Terminology - let’s get things straight

Let’s begin by expanding our understanding of trust by examining the following four areas:

- Dictionary definitions

- Social trust

- Perspectives on trust

- DLT system trust

1. Dictionary definitions

If we examine the definitions of trust in some of the most popular dictionaries (Merriam-Webster, Cambridge, Britannica, Collins, and Dictionary.com), we find that they all fall into two main categories:

1. Personality, character, and ability

- assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something

- one in which confidence is placed

- the belief that you can trust someone or something

- belief that someone or something is reliable, good, honest, effective, etc.

- Your trust in someone is your belief that they are honest and sincere and will not deliberately do anything to harm you

- reliance on the integrity, strength, ability, surety, etc., of a person or thing; confidence

- a person on whom or thing on which one relies

2. Safekeeping, charge, custody, and care

- something committed or entrusted to one to be used or cared for in the interest of another

- a charge or duty imposed in faith or confidence or as a condition of some relationship

- in trust: in the care or possession of a trustee

- an arrangement in which someone’s property or money is legally held or managed by someone else or by an organisation for usually a set period of time

- the condition of one to whom something has been entrusted

- something committed or entrusted to one’s care for use or safekeeping, as an office, duty, or the like; responsibility; charge

- the obligation or responsibility imposed on a person in whom confidence or authority is placed

These two categories complement one another. You would never entrust your assets to a person if you lacked confidence in their character, for instance. You could also say that at level 1, you trust a person to have a favourable attitude towards you, to tell the truth, to be able to complete an assigned task, etc. So, let’s refer to the first level of trust as ‘shallow trust’.

However, the second level of trust (let’s call it ‘deep trust’) goes even further and is demonstrated when you entrust someone with something of great value to you. For instance, a secret, responsibility over one’s assets, responsibility over one’s life or the life of a loved one, etc. Therefore, the second level of trust is more profound than the first.

In a DLT system, deep trust is required, as shallow trust in third-party intermediaries is insufficient to entrust one’s assets to them.

2. Social trust

The sources listed below all indicate that there are two distinct types of social trust:

- Social trust: its concepts, determinants, roles, and raising ways

- The Impact of Trust on the Quality of Participation in Development

- Impact of Institutional Trust on Subjective Well-being in Selected Asian Countries

- Influence of Interpersonal and Institutional Trust on the Participation Willingness of Farmers in E-Commerce Poverty Alleviation

- The Relation between Interpersonal and Institutional Trust in European Countries: Which Came First?

- OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust

The above publications all differentiate between interpersonal and institutional trust.

In the first chapter of his book titled Social Trust and Economic Development, O. Yul Kwon defines the two subtypes of trust as follows:

Interpersonal Trust

Individuals’ expectations of other members of society to act and behave in a way that is beneficial to these individuals or at least not detrimental to them. Interpersonal trust reflects people’s subjective perspective of others’ reliability without legal commitment, and involves a degree of risk and uncertainty. Hence, trust involves two components: expectations and willingness to take risky actions based on the expectations.Institutional Trust

Institutional trust is the confidence of citizens in institutions. Citizens expect institutions to perform efficiently, effectively, fairly, and ethically in accordance with the roles assigned to them by law or with social norms in the eyes of citizens. People’s trust in institutions is not the same kind of trust as that between each other as individuals. Interpersonal trust is based on immediate, first-hand experience of other individuals, whereas institutional trust is more generally learned indirectly and at a distance, usually through the media and social intercourse. Interpersonal trust is an expression of the basic features of trusting personalities, whereas institutional trust is based on an evaluation of the performance of institutional functions.

Despite the fact that we were unable to locate any text in which Satoshi distinguishes between interpersonal and institutional trust, the impression given is that he had no problem with interpersonal trust, but only with institutional trust.

Since it is impossible to eliminate trust from a digital money system, we can conclude that every digital money system always falls into one of these two categories of trust. Banks and other traditional financial institutions clearly belong to the institutional trust category, whereas DLT systems, which can be operated by ordinary people make use of interpersonal trust.

3. Perspectives on trust

As noted at the outset of this article, Satoshi identifies trust as the major issue, as evidenced by the following quote:

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work.

But what kind of trust was Satoshi referring to in his criticism of conventional currency? On the basis of all of his published statements and comments, one can infer that he was referring to ‘blind trust’ (i.e. blind faith) in the majority of instances.

A system in which compliance with the rules of all system operations is easily verifiable is always superior to a system based on blind trust. At least when the outcome is essential and matters more than the relationship, as is the case with a money system. This is why we must be able to verify the correctness of all operations in a money system.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible for the average person to obtain deep insights into the internal operations of banks and financial institutions, let alone influence them, which is why these systems demand a high level of blind trust from their users.

But if blind trust is required to make a money system work, then trust in the operators becomes a dependency. And according to Nick Szabo personal property has not and should not depend on trusted third parties, because they are security holes. Therefore, if a system depends on blind trust to function, it has a dependency on security holes. And since security holes pose risks to the system’s users, such a system is inherently dangerous. This obviously discourages users from utilising such a system.

Instead, we require a money system that is widely trusted (and therefore utilised) by as many people as possible. To accomplish this, a money system must minimise the risk for users, which necessitates as few security holes as possible, which in turn requires a minimal dependence on blind trust in the system.

So, what we actually want is blind trust dependency minimisation rather than trust minimisation.

This leads us to assume that every time Satoshi spoke critically about trust, he was criticising the dependence on blind trust.

Here are two examples to illustrate this point:

- When someone says: “Trust me please”, and you have no option but to comply, then this is a dependence on blind trust.

- On the other hand, when someone says: “Don’t take my word for it, see for yourself” and provides all the evidence required, then you’re not required to trust them blindly, which builds trust (as long as the evidence matches their words).

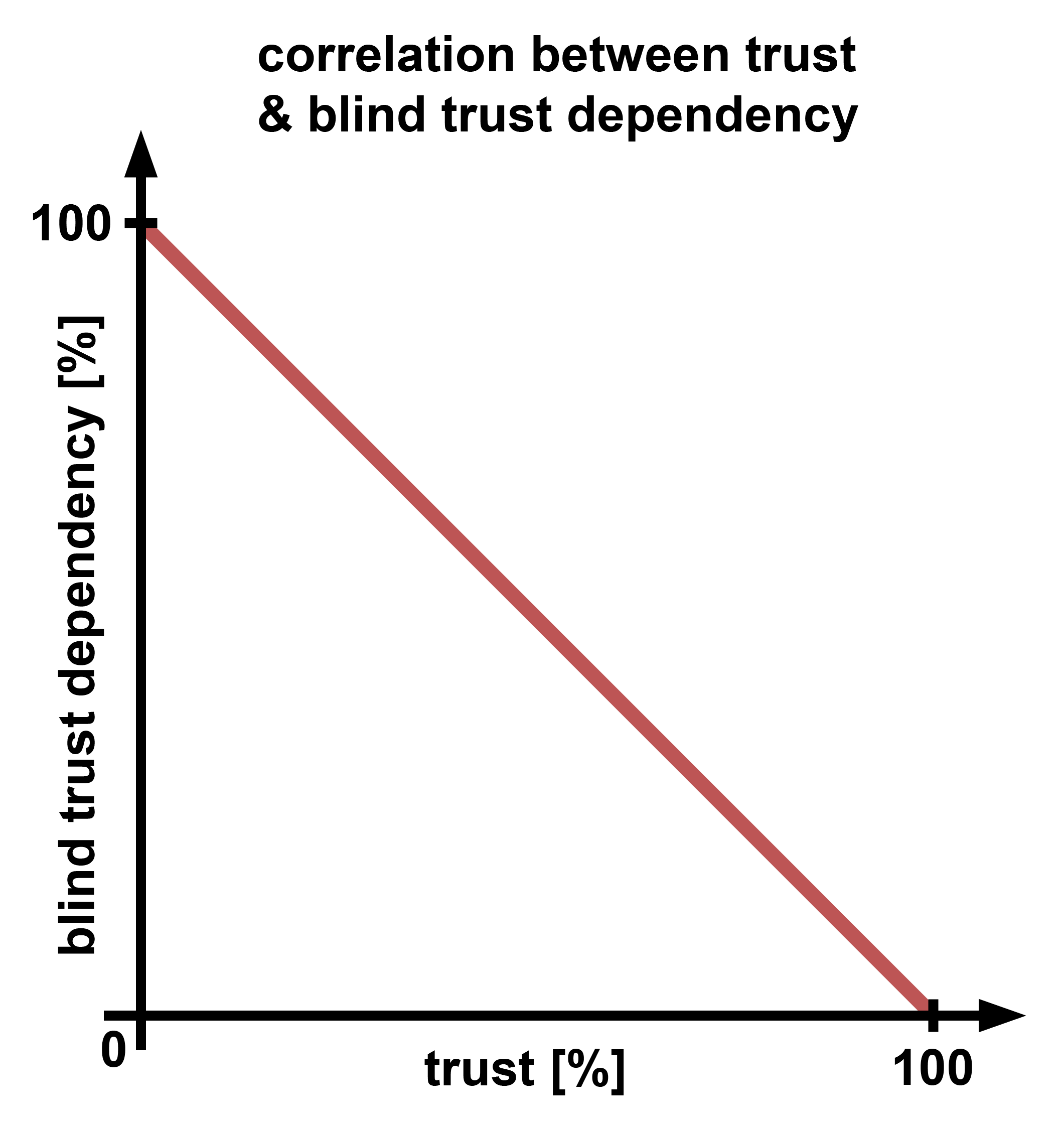

Moving forward, it is important to differentiate between ‘trust’ and ‘blind trust dependency’, because they are negatively correlated to each other. The lower the dependency on blind trust the higher the trust in that system, and vice versa.

In other words, every social system (especially money systems) relies on the trust of its users. Whether it be blind trust, or trust based on the users’ ability of verification of, and participation in the operation of the system. The total amount of trust in any social system is always a combination of these two components (i.e. the sum of the two values of both axes of the graph shown above, so to speak).

In summary, these are the two perspectives on trust:

Good trust:

Voluntary trust is a positive quality in and of itself! It makes users feel safer, attracting more users as a result.Bad trust:

Dependence on blind trust is bad! It increases the security risk for users, thereby discouraging their use of such a system.

So, the question is now: how to replace blind trust dependency with user-generated trust? To determine this, we must identify the elements that inspire user confidence in a DLT system.

4. DLT system trust

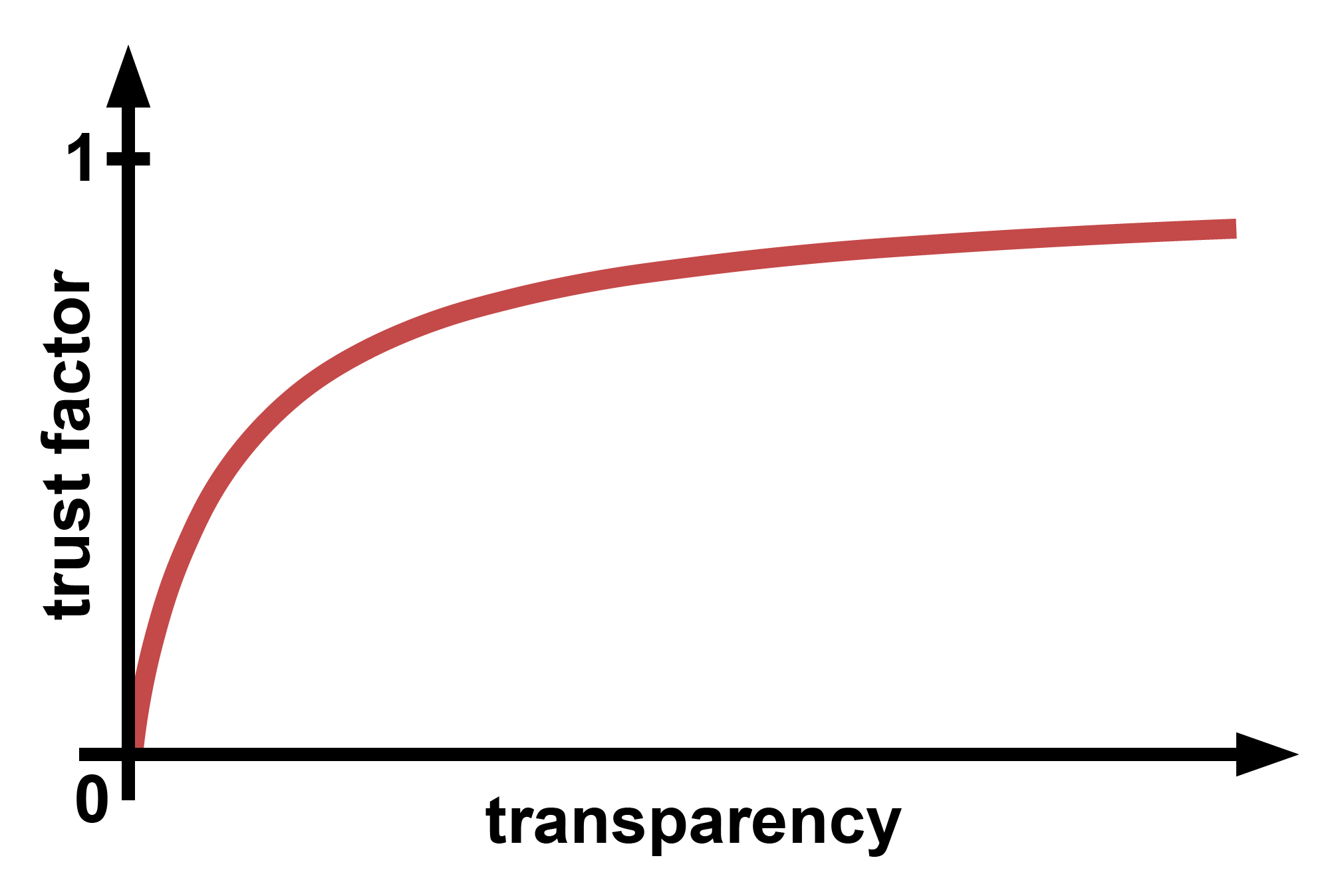

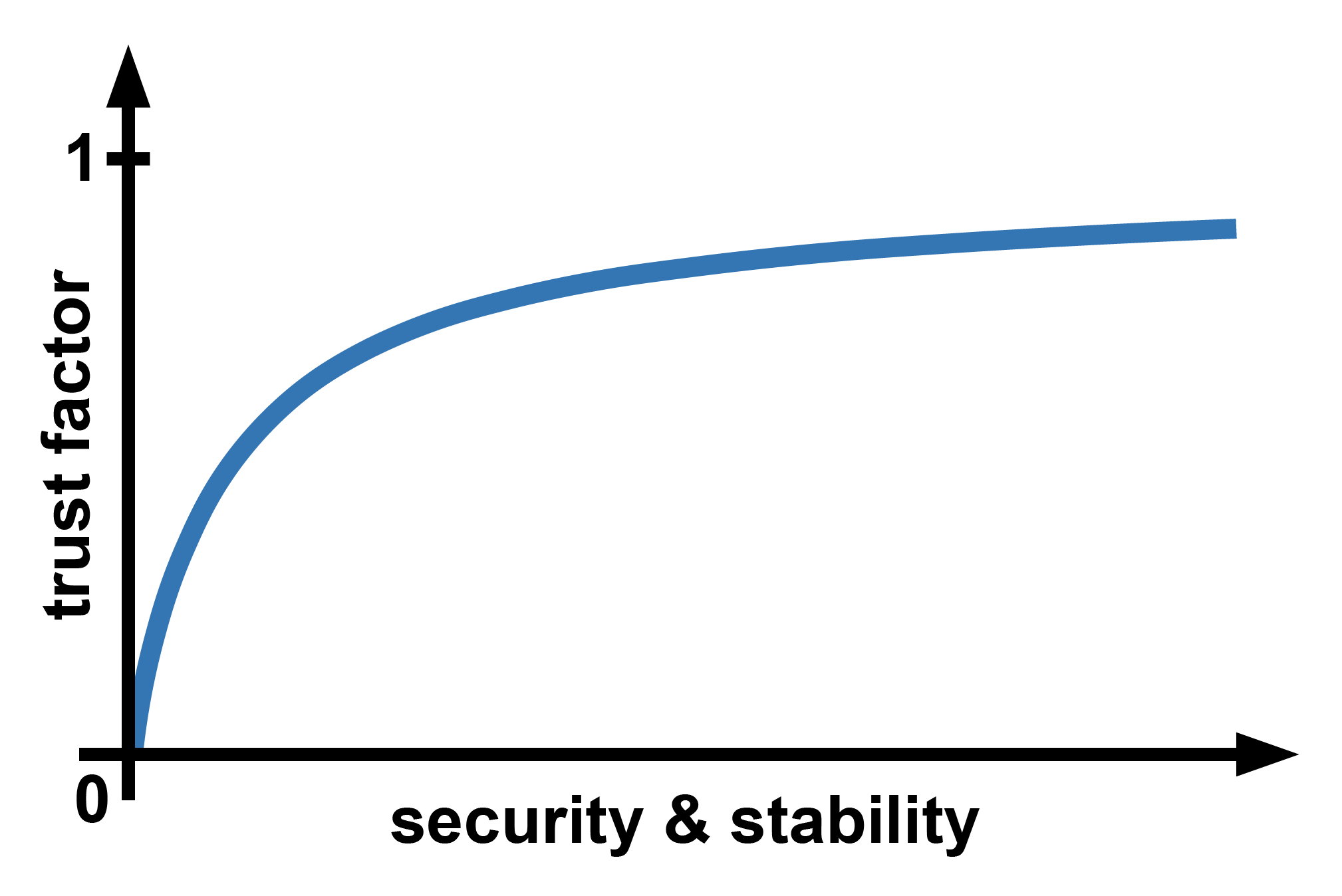

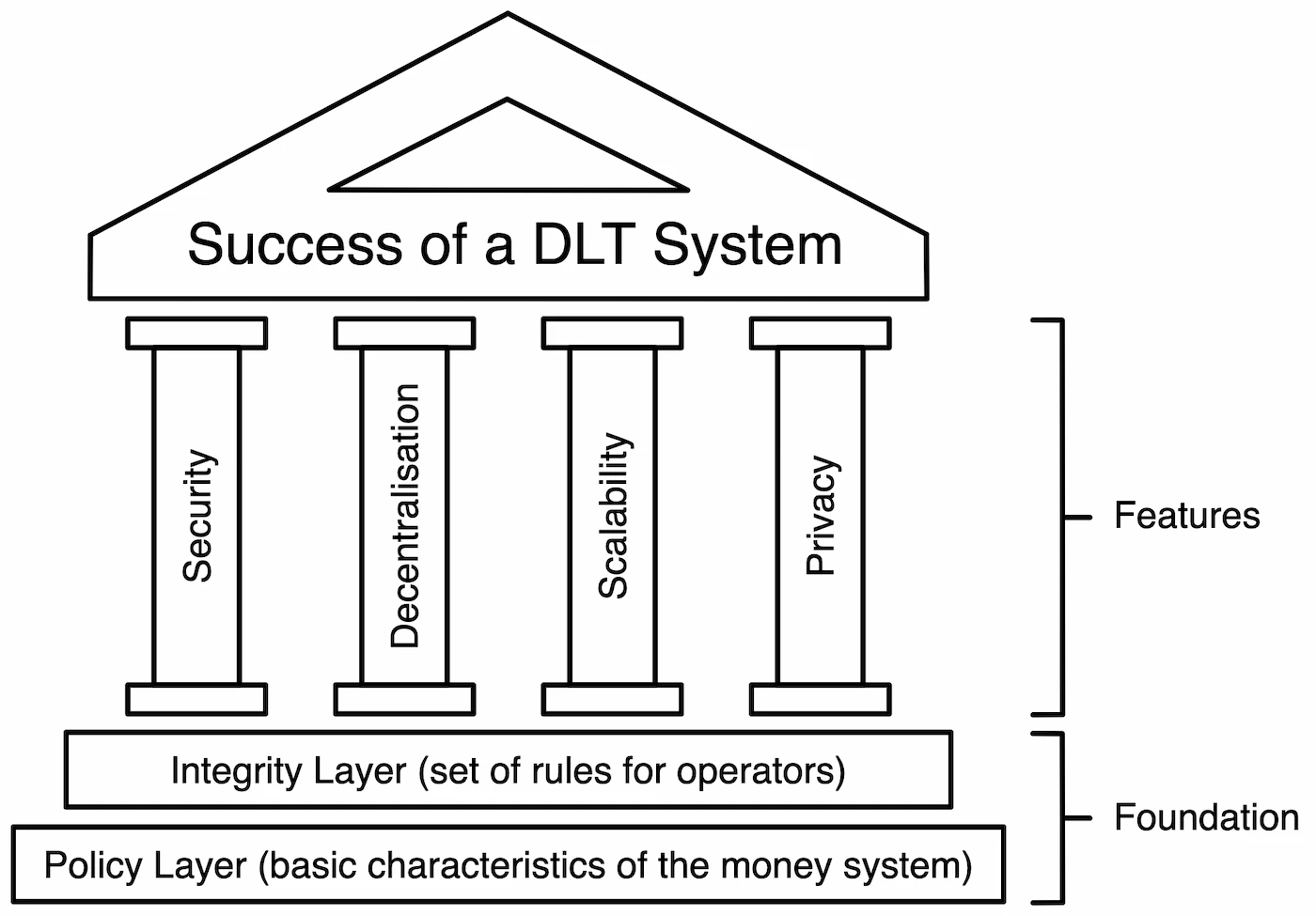

The overall trust of a DLT system consists primarily of the five components listed below:

- Transparency of the technology

- Security & stability of the technology

- Decentralisation of operators

- Liability of operators

- Privacy of users

In the previous section What about blockchain, cryptography, decentralisation…? we did not address the security and stability of the technology, as we can assume that the IT systems of legacy financial institutions are equally secure and stable from a technological point of view. Thus, this isn’t an advantage of DLT systems over the legacy financial institutions. However, this does not diminish the importance of this element in the overall trust in DLT systems.

To make it as simple as possible for users to hold trust in a money system, all five of these components are equally (or similarly) vital. It is inadequate to be strong in only four areas, because as soon as one area is neglected, trust in the system as a whole decreases proportionally.

Therefore, if any of the following conditions are met, the system’s overall credibility declines considerably:

- Source code that is not open; no well-defined and publicly visible rules; or inability to verify compliance with said rules;

- utilisation of unstable technology or frequent system outages;

- a person or small group can exert substantial influence over the system’s operation, rules, or development;

- the operators of the system need not fear any consequences in the event of fraudulent activity; or

- all transaction details (who acquired what, when, and where), as well as the identities of those conducting the transactions, are publicly accessible.

Therefore, a system with no transparency, an insecure or unstable technology, very little or no decentralisation, nothing to lose for its operators in the event of fraudulent behaviour, and no privacy for its users has the lowest level of trust and is therefore the most dangerous system for its users.

Compared to this, a system with complete transparency, a very safe and stable technology, high degree of decentralisation, high liability of its operators (bad actors have a lot to lose), and high user privacy protection enjoys the highest level of trust and is thus the safest system for people.

Despite the difficulty (or perhaps impossibility) of quantifying trust in a DLT system, let’s attempt it. A simplified yet descriptive method for determining the overall trustworthiness of a DLT system could be to:

- Evaluate and rank each trust area (this is partially subjective)

- Determine the respective trust factor between 0 and 1 for each area

- Multiply all of these trust factors

On the X-axis of the subsequent graphs, a value can be assigned based on the degree of transparency, security & stability, decentralisation, operator liability, and user privacy. The Y-axis can then be used to determine the trust factor of the trust area based on the X-axis’ value.

These five trust factors must be multiplied together to determine the DLT system’s overall trust. Thus, the formula could appear as follows:

Consequently, even if only one of the trust factors were to be zero, the system’s overall trustworthiness would also be zero percent.

Now that we have clarified some preconceptions about trust, let’s get back to the underlying cause of the problem relating to our current monetary system.

Understanding the root problem

Some interested readers may be wondering why we have only referenced Bitcoin and none of the altcoins (alternative cryptocurrencies) thus far. However, there is a good reason for this, as aptly described by Bryan Solstin in an interview with Robert Breedlove:

There are so many altcoins out there that are trying to be better than Bitcoin. And as a politician I’m running to fix a broken monetary system. Nothing else is sufficiently decentralised. Nothing else can fix that problem. Only Bitcoin can do that. It doesn’t matter if you have additional features or functions. Only Bitcoin fixes the broken monetary system.

Thus, the issue is the broken monetary system. And according to a recent Fidelity report, Bitcoin is the most secure, decentralised, and sound digital money currently available. That’s why other DLT solutions are often called DINO (decentralised in name only).

Here’s is the summary of the Fidelity report (page 2):

- Bitcoin is best understood as a monetary good, and one of the primary investment theses for bitcoin is as the store of value asset in an increasingly digital world.

- Bitcoin is fundamentally different from any other digital asset. No other digital asset is likely to improve upon bitcoin as a monetary good because bitcoin is the most (relative to other digital assets) secure, decentralized, sound digital money and any “improvement” will necessarily face tradeoffs.

- There is not necessarily mutual exclusivity between the success of the Bitcoin network and all other digital asset networks. Rather, the rest of the digital asset ecosystem can fulfill different needs or solve other problems that bitcoin simply does not.

- Other non-bitcoin projects should be evaluated from a different perspective than bitcoin.

- Bitcoin should be considered an entry point for traditional allocators looking to gain exposure to digital assets.

- Investors should hold two distinctly separate frameworks for considering investment in this digital asset ecosystem. The first framework examines the inclusion of bitcoin as an emerging monetary good, and the second considers the addition of other digital assets that exhibit venture capital-like properties.

According to this Fidelity report, Bitcoin’s success as a monetary good does not render all other DLT solutions useless. “Rather, the rest of the digital asset ecosystem can fulfill different needs or solve other problems that bitcoin simply does not.”

However, in this article we will only consider Bitcoin, as we are particularly interested in the solution to the underlying problem that sparked the entire DLT movement.

But before examining solutions such as Bitcoin, it is crucial to first comprehend the problem surrounding our current monetary system. One can only recognise the value of a solution after having grasped a thorough understanding of the problem at hand. In other words: The greater a person’s awareness of the harmful effects of centralised money, the sooner they recognise the advantages of a decentralised money system. If people are not yet aware of the gravity of this issue, the result is often reflected in articles such as There’s No Good Reason to Trust Blockchain Technology.

Regarding trust, the article has some interesting food for thought, but it becomes clear that the author (Bruce Schneider) is unaware of the immense implications of centrally controlled currencies, which is precisely why he does not recognise the value of sound money. Nevertheless, he makes a few valid assertions about trust, including:

Trust is essential to society. As a species, humans are wired to trust one another. Society can’t function without trust, and the fact that we mostly don’t even think about it is a measure of how well trust works.

This is very true. At least until the point at which trust begins to erode. The vast majority of people in the world are not as privileged as Bruce Schneider, who has the prerogative of living in a country and using a financial system that has not yet betrayed his trust (at least not to the extent that he would have noticed). However, once he also suffers this threat, he will likely no longer be able to claim that he “mostly [doesn’t] even think about it”.

Therefore, we only start considering the role that trust plays in any given situation, relationship, or system when it is removed. As soon as trust is broken, it often becomes painfully apparent. This is precisely what occurs to countless people all over the world, every single day.

Causes of the breaches of trust

Most would likely agree that we live in the most prosperous time in human history today. Poverty, sicknesses, and ignorance are receding throughout the world, due in largely to advances in economic freedom. However, we view the growing concentration of power in the financial sector as one of the greatest obstacles in preventing us from achieving our objective of expanding freedom, prosperity, justice, and peace for all human beings.

A lot of people have already noticed that there is something wrong with our incumbent monetary system, but they can’t quite put their finger on it. They just notice that the ever-growing mountain of debt can never be paid back, that there is a lack of money everywhere, that the social issues in our society are increasing, and that the inequality in this world seems to be getting worse and worse. Even without knowing the exact causes, it is clear to many that these issues must somehow be linked to our monetary system, which has led to the aforementioned widespread mistrust of financial institutions.

Satoshi’s initial public announcement of Bitcoin touches on this:

The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts.

Within this statement, Satoshi criticises the following three points:

- debasing the currency

- lending [the money] out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve

- letting identity thieves drain our accounts

In the past three years, the majority of nations have printed more money than ever before (or, to be precise, entered some large numbers into a software system). And the ramifications of these monetary policies on the middle and lower strata of the population are becoming increasingly severe in many countries.

Elon Musk commented on this in April 2022 by stating:As the saying goes, when the government first prints money, everyone feels like a winner, but in the end no one does.

Ross Hendricks also summed it up well in his LinkedIn post There’s nothing more expensive than “free money”.

However, Satoshi’s criticisms merely represent the tip of the iceberg. Every year, new banking scandals are uncovered, and the number of individuals suffering (whether aware of the cause or not) from the current fiat monetary systems continues to rise. This heavily counteracts the development of economic freedom (which is the main driver of prosperity).

We are not talking about small local community banks, credit unions, etc. but rather big and powerful financial institutions such as:

The longer you study centrally controlled fiat currencies, the more you realise their unfathomable dark side.

Here are just a few of the repercussions of our current monetary system:

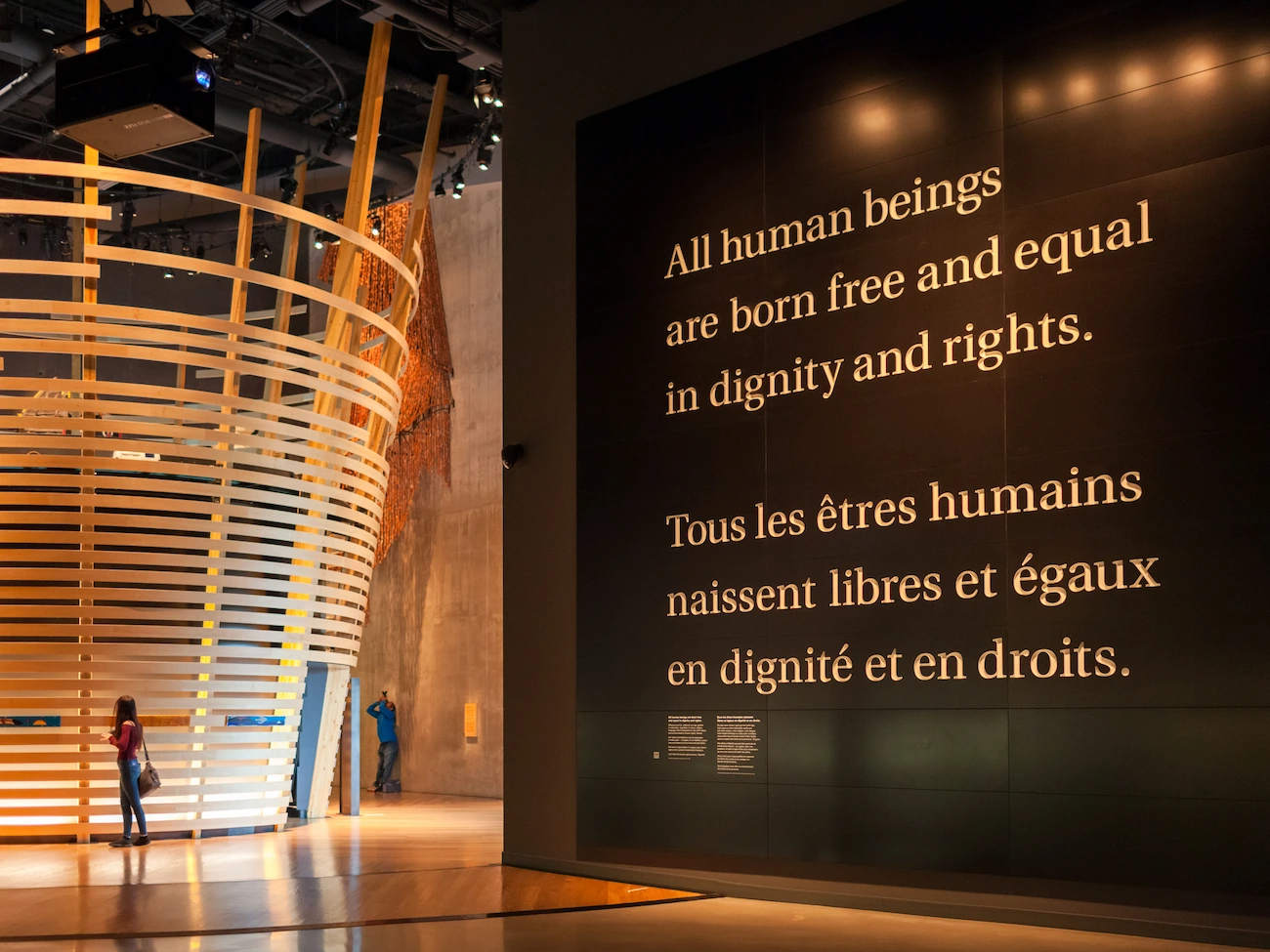

- Human rights violations

- Property

- Expansion of the money supply causes inflation which is a secret theft of time and money

- Printing money is a wealth redistribution scheme from the poor to the rich

- Governments can freeze bank accounts if they have economic issues (like in Argentina in 2001)

- All fiat currencies are collapsing

- Central banks are looting their host nations

- Governments destroy the prosperity of their citizens

- Freedom of speech

- Privacy

- Liberty

- Freedom from slavery

- Equality and non-discrimination

- Security and peace

- Rest and leisure

- Freedom of residence

- Property

- Economic exploitation (of developing countries)

- Environmental degradation

- The dirty investments of major banks around the world

- Banks lent $2.6tn linked to ecosystem and wildlife destruction in 2019

- World Bank and IMF actions have immense environmental consequences

- Many banks are well-documented financiers of the climate crisis

- Global banks ‘failing miserably’ on climate crisis by funneling trillions into fossil fuels

Despite these warnings, Woodrow Wilson still signed the 1913 Federal Reserve Act. A few years later he wrote:I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies.

Josiah Stamp, a director of the Bank of England (the central bank of the United Kingdom), even went so far as to claim:I am a most unhappy man. I have unwittingly ruined my country. A great industrial nation is controlled by its system of credit. Our system of credit is concentrated. The growth of the nation, therefore, and all our activities are in the hands of a few men. We have come to be one of the worst ruled, one of the most completely controlled and dominated Governments in the civilized world no longer a Government by free opinion, no longer a Government by conviction and the vote of the majority, but a Government by the opinion and duress of a small group of dominant men.

Banking was conceived in iniquity and was born in sin. The bankers own the earth. Take it away from them, but leave them the power to create money, and with the flick of the pen they will create enough deposits to buy it back again. However, take away from them the power to create money and all the great fortunes like mine will disappear and they ought to disappear, for this would be a happier and better world to live in. But, if you wish to remain the slaves of bankers and pay the cost of your own slavery, let them continue to create money.

Not to mention CBDCs, which many agree will be a total human rights disaster. They are worse in every aspect of the human rights violations mentioned above than the current financial fiat system. Despite this, many countries already have a first version in operation, or are currently in the process of testing or developing their own CBDC.

Some may wonder how all this can still be happening in the 21st century? Well, since money is power, the centralisation of money is therefore centralisation of power. And as accurately observed by Lord Acton:

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

This maxim is always true independent of the century we live in.

As the tendency towards centralisation continues to grow the serious harmful implications of centralised fiat currencies on the daily lives of a large number of people and our environment will intensify even further.

So, the real problem is that the powerful financial organisations have brazenly abused the trust of the public many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many times and have no intention of restoring it. But strictly speaking, it is not the financial institutions themselves (since institutions cannot act on their own accord) but their operators who have abused the public’s trust. Reality has demonstrated that the untouchable operators of these systems tend to act primarily to their own advantage (or that of other influential groups of individuals) and to the detriment of the general public. Unfortunately, this always results in greater poverty for the vast majority of the population and greater wealth for only a few. In other words, it’s an unjust redistribution from the poor to the rich.

This has understandably led to widespread distrust of these financial institutions and the only logical consequence is that the disappointed and frustrated people will seek alternatives.

Regardless of the political spectrum people associate themselves with, the point on which all of them would agree is there should be more prosperity and less poverty in the world. Thus, all people agree on this essential political goal, with only differing opinions on how to get there.

However, increasing centralisation in the financial sector is certainly not getting us any closer to our common goal of less poverty and more prosperity for everybody. As documented throughout this article, many of our socio-political problems stem from our fiat monetary system.

If we want to have a chance of tackling any of the other big social issues we’ve got to figure out the money issue [first].

Ben Dyson

Michael Saylor also gave weight to the fact that the majority of the world’s issues are caused by our fiat monetary system in a recent interview with Lex Fridman:

I believe that Bitcoin is a massive breakthrough for the human race that will cure half the problems in the world and generate hundreds of trillions of dollars of economic value to the civilization.

German banking and development economist Prof. Richard Werner is even confident that Keynes’s prediction that “we would only have to work 15 hours a week” would have come true if the current centralised monetary system had not led to such an unjust distribution of wealth.

But, if we know that the malfeasance, failures, and even crimes of powerful financial institutions result in less prosperity and increased poverty overall, shouldn’t we all do everything in our ability to prevent this? Especially since the next financial crisis is already looming.

Everybody, the left and the right, you know, the communists and the fascists, they’re all fighting about wealth. Because everybody is fighting about wealth when you have a downturn.

Ray Dalio

We presume that the majority of individuals would prefer to prevent this, but just don’t know how.

The need for a free money market

The first obvious conclusion is that alternatives are required. People will only be able to choose their preferred money when widely accepted alternatives are available. The phrase ‘competition is good for business’ applies not only to the commercial world, but also to the free market in general, which includes exchange and payment methods. However, not allowing people to choose their preferred money and forcing a specific money system on them is coercion, and hence unethical and immoral, as particularised above.

This is why Satoshi’s goal with Bitcoin is to provide an alternative to the state’s monopoly on currency.

By allowing people to develop their own money systems and freely choose their preferred one, the best money system will win in the long term. And, as long as the money market is free and fair, the money that delivers us humans closest to the aim of less poverty and more wealth for all will win (which will undoubtedly be the hardest form of money). This would then redistribute power back to the people.

Brian P. Simpson discusses the benefits of a free monetary and banking system in detail in chapter 5 of his book Money, Banking, and the Business Cycle (Ch.5: The Characteristics and Effects of a Free Market in Money and Banking).

Its main message is well summarised in the abstract of this chapter:

This chapter shows that a free monetary and banking system means absolutely no government interference in money and banking. It discusses what is meant by “no government interference.” Such a system is unprecedented in history, except for possibly the very first banks in ancient Greece or fourteenth-century Italy. From the very beginning, or very shortly thereafter, governments interfered in monetary and banking systems to gain advantage for themselves and those they wanted to favor. This interference existed in the form of minting coins, debasing the currency, allowing banks to suspend payment when payment was contractually required on demand, raiding bank vaults, and so on. A free market in money and banking will lead to a level of stability in the economy that will make the economic system seem boring compared to today, since it will virtually eliminate monetary induced financial crises, recessions, and depressions. Developments in the economy will still be exciting; however, the excitement will be confined to rapid rates of economic progress; innovations in products and methods of production; the development of new technologies; the exploration of space and the colonization of moons, planets and other solar systems by private individuals; and a rapidly rising standard of living.

And, unlike the incumbent monetary system, the standard of living would not rapidly rise for just a few people, but for everyone!

If you want to learn more, we highly recommend the money and banking works on the Satoshi Nakamoto Institute’s Literature page, particularly What Has Government Done to Our Money? and The Mystery of Banking by Murray N. Rothbard.

Despite all this, some people are concerned that a money system that is not regulated by their government may encourage crime and so result in a greater crime rate. This concern, however, is unfounded for two reasons:

- The growth of legitimate cryptocurrency usage is far outpacing the growth of criminal usage. Or to quote from the “_Crypto is Bad for (Bad) Business_” section of the Messari Report for 2022:

The whole “crypto is for criminals” schtick is categorically false - a myth perpetuated only by the ignorant and the willfully misleading. As mentioned earlier, illicit activity comprises just 0.34% of crypto transactions according to Chainalysis, lower than incidence of illicit activity in “regulated” financial services, where banks have been notoriously effective money launderers for cartels and ultra-rich tax evaders.

It is clearly much more difficult to establish a link between the crime rate and the feasibility of crime than it is to establish a link between the crime rate and the policies of the individual government. A study on the relationship between quality of governance and occurrence of crime comes to the following conclusion:

The findings suggest that different indicators of governance are significantly related with different categories of crime such as homicides, robbery, kidnapping and burglaries. Almost all four types of crime are affected equally by the governance indicators. Socioeconomic conditions, corruption, law and order, external conflict, investment profile and ethnic tensions are significantly related with crime. Among all the economic variables, only per capita GDP and income inequality had a significant impact on homicide.

Consequently, combating crime with a centralised monetary system would only address the symptoms and not the underlying cause.

And even if a government-controlled monetary system made it simpler for law enforcement to crack down on criminals, we still believe that defending the following is far more important:

- Human and property rights;

- developing countries; and

- the environment.

In fact, not those who are opposed to concentration of power (as in the example of central banking) struggle to justify their position, but those who continue to support central banking and power concentration despite being aware of the human rights violations, environmental degradation and tyranny of entire nations that come along with it.

Or as Alex Gladstein puts it:

Maybe you don’t need Bitcoin and maybe you don’t understand Bitcoin and maybe PayPal, Venmo or your bank account serve your needs just fine. But don’t write off Bitcoin as simply a vehicle for financial speculation [or a tool for criminals]. For millions of people around the world it’s an escape hatch from tyranny and nothing less than freedom money.

… and:

If we keep growing this… and if Bitcoin thrives, humans will have a money:

- that can’t be censored by authorities;

- that can’t be devalued by governments;

- that can’t be monopolised by corporations;

- that can’t be easily mass surveilled;

- that can’t be stopped by borders; and

- that can be accessed by anyone.

And that’s why Bitcoin matters for human rights.

Does this settle the question of the raison d’être of cryptocurrencies (or decentralised money systems in general) once and for all?

One thing is for certain: In the coming years, we will be forced to endure the negative impacts of centrally controlled currencies. This will result in a growing need for alternative money systems. It was precisely for this reason, Satoshi created Bitcoin during the last financial crisis.

The motivation behind this article

So, if a solution to this problem already exists, what is the purpose of this article?

Bitcoin promised to be a peer-to-peer electronic cash system, but as we have seen in recent years, Bitcoin no longer fulfils that promise.

You read and hear virtually everywhere that Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer payment method, i.e. a direct transaction between payer and payee. As previously demonstrated, this is technically impossible for a digital money system. Peer-to-peer merely describes the type of network used for communication between the Bitcoin network’s operators, not the manner in which payments are settled between two parties (as is possible in the case of gold).

However, this part was not the motivation for this article, but rather the assertion that Bitcoin is an “electronic cash system”. Bitcoin cannot be considered an electronic cash system suitable for micropayments if it lacks several of the essential features of cash, such as:

- no scalability limits

- instant transactions

- final transactions (once cash is handed over the transaction is final)

- no transaction fees (or consistently very cheap)

- energy efficient

- untraceable

All of these characteristics are needed for a monetary good to be viewed as a serious alternative to the current fiat monetary system. If not, it’s just another asset class (albeit a superior one to all the other asset classes, as Bitcoin is quite evidently an above-average store of value so far). Nevertheless, based on all of Satoshi’s publications, we may conclude that he never intended to create a new asset class, but rather a decentralised money system with all the characteristics of sound money (i.e. a money system that cannot be devalued). Satoshi probably just didn’t expect such a high demand for Bitcoin, so that one day it will become less attractive as a medium of exchange and mainly be used as a store of value.

Since the very essence of money is its utilisation, we must facilitate these cash-like characteristics to the greatest extent possible. As Dr. Saifedean Ammous says in his book The Bitcoin Standard (page 155):

As money is acquired not for its own properties, but to be exchanged for other goods and services [...]

Or as Ludwig von Mises puts it:

[...] Money has no utility other than that arising from the possibility of obtaining other economic goods in exchange for it.

Everything else is not money.

One could argue that (1) Bitcoin need not be a good medium of exchange in order to be a good store of value, or that (2) we place too much weight on Satoshi’s intentions. Let’s examine these two arguments separately:

Yes, it is true that a technology does not necessarily have to be used exclusively for the reason for which it was designed. If a technology is also well-suited for a different purpose, of course it can be employed for that purpose as well. And in the case of Bitcoin, it has performed exceptionally well as a store of value thus far. But if Bitcoin can only be used in a limited capacity as a medium of exchange, it cannot replace the fiat currency systems. Because for this it would have to exhibit the cash-like characteristics listed above. One does not drive global adoption of Bitcoin by investing one’s savings in Bitcoin and waiting for its appreciation, but by using it for day-to-day payments and educating others about the problems and solution to our broken monetary system.

It is not necessary to be a fundamentalist of the Bitcoin white paper to believe that the medium of exchange function is as vital for a monetary good as the store of value function. The real issue that has led to the whole Bitcoin (BTC) vs Bitcoin Cash (BCH) debate is that Bitcoin by itself can only be good at one of these two functions. And logically, the market chose BTC, because there are already plenty of good media of exchange out there, but there is no comparable store of value to Bitcoin that has all the characteristics of sound money. But what we seek is a monetary good that is at least as good as Bitcoin at storing value and also possesses the features of cash. Because, regardless of Satoshi’s viewpoint, the ability to be a scalable medium of exchange is crucial for a global money system. There’s absolutely no reason why somebody wouldn’t want a money system to be a good medium of exchange so long as the store of value function isn’t adversely affected. To the contrary, if a superior store of value is also a superior medium of exchange, this will increase usage and thus adoption, which in turn will be reflected in the price. In other words, even someone who owns bitcoin primarily for the appreciation of its value should be a strong proponent of the medium of exchange function, because it accelerates the intended process.

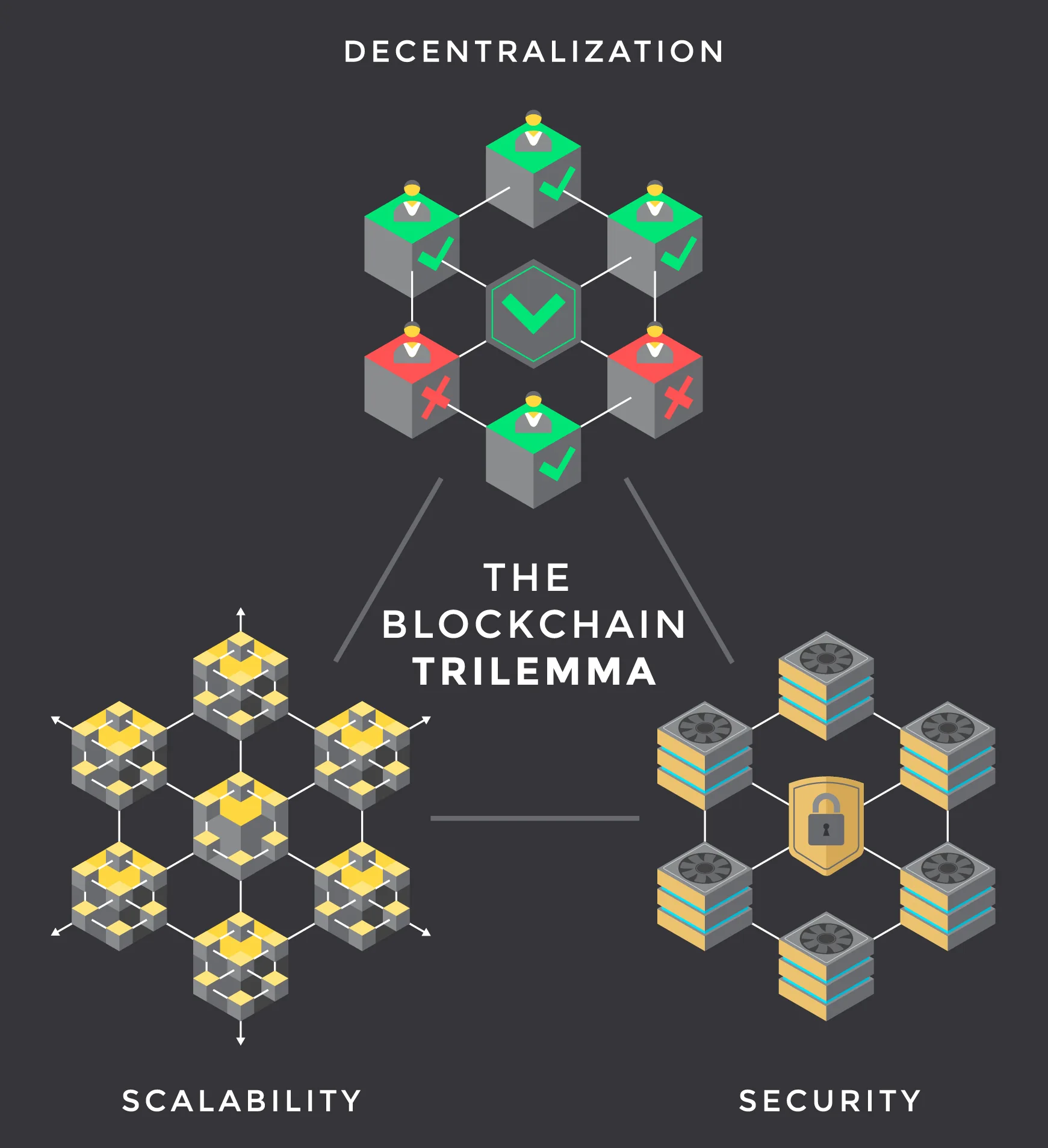

Unfortunately, Bitcoin will never be a good medium of exchange on layer 1 (i.e. with its main blockchain). Because of this, thousands of Bitcoin alternatives as well as layer 2 solutions have emerged, with many of them attempting to remedy Bitcoin’s scalability issue. To acquire some of these cash-like characteristics, Bitcoin’s competitors have had to cut back on either security or decentralisation, which of course has not proven to be a successful tactic.

Sadly, layer 2 solutions are not an effective remedy, as all known layer 2 concepts and solutions introduce new shortcomings, such as:

- Serious trade-offs in security and/or decentralisation

- Additional on-boarding friction

- Less liquidity on the primary blockchain

- Significant increase in the complexity of the system (which opens up all sorts of attack vectors)

- Bitcoin Lightning Network specific tradeoffs:

- Lightning Network is evolving towards an increasingly centralised architecture (which would violate Bitcoin’s fundamental promises of security, censorship-resistance, neutrality, etc.)

- Confirmation of a transaction on the Lightning network can still take up to a minute, which isn’t fast enough for retail payments

- Risk of losing money without doing anything wrong (which can be especially painful for people on low incomes)

- Lightning’s routing causes privacy issues and doesn’t protect from surveillance

- Lightning Nodes have to remain online at all times

- If a Lightning node is offline for a longer period of time a malicious peer may be able to steal some of their money

- More than 5 years after the launch of the Lightning Network, the user experience is still poor

- Even if almost all transactions of all users take place in the Lightning network and only 3 opening or closing channel transactions per user per year are carried out on layer 1, in ideal circumstances Bitcoin (with its current block size of 1MB) can still only support about 35 million users (see Lightning Network Paper (page 53))

- Narrow operating range: The Lightning Network doesn’t work very well if it is not actively used by a lot of people (i.e. if it doesn’t have many well-funded open payment channels). But without an increase of Bitcoin’s current block size (which would require a hard fork supported by the majority of the Bitcoin community), the Lightning Network isn’t able to scale globally.

- Other risks like: Improper Timelocks, Forced Expiration Spam, Coin Theft via Cracking, Data Loss, Forgetting to Broadcast the Transaction in Time, Inability to Make Necessary Soft-Forks, Colluding Miner Attacks (see Lightning Network Paper (page 49 onwards))

- … and many more security concerns as well as design issues

As this article focuses primarily on Bitcoin as the solution to the broken monetary system, we have paid special attention to the Lightning Network in the above list, as it is currently the most promising and widely used layer 2 technology for Bitcoin.

To fix the broken monetary system, we need a solution that can easily scale globally (i.e. be used by everyone on earth without reaching its limits). If a technology cannot achieve this, it is not a solution! Because a system that can only be used by a small fraction of the global population means, conversely, that it is not a solution for the majority of people, leaving them defenceless against the effects of the fiat monetary system.

If the Lightning Network could easily scale globally, this article would be superfluous. However, according to its creators, the Lightning Network is struggling to meet this important requirement. Let’s look at the much-discussed passage from the conclusion of the Lightning Network white paper (page 55):

If all transactions using Bitcoin were conducted inside a network of micropayment channels, to enable 7 billion people to make two channels per year with unlimited transactions inside the channel, it would require 133 MB blocks (presuming 500 bytes per transaction and 52560 blocks per year).

We now have 8 billion people on earth, which would increase the assumption from 133 MB blocks to around 150 MB blocks. In addition, we believe there are several reasons why two channels per year is not realistic. A more realistic scenario would be one channel per month, which would increase the required block size to over 900 MB.

Even if we were to use proposed solutions such as batch opening, channel factories, splicing, etc. and were able to reduce the on-chain footprint by 90%, blocks of at least 15 MB or realistically closer to 90 MB would still be required, which is many times the current block size of Bitcoin.

With or without on-chain footprint optimisations, it always affects either the decentralisation (and thus security) or the usability (making the Lightning network inaccessible to many people) of the Bitcoin network.

All of the above is why we have serious doubts about the technological feasibility of developing a layer 2 solution that is as secure, decentralised, and accessible as the underlying layer 1; otherwise, the layer 2 solution could simply be used as the main blockchain. But if it’s not as secure, decentralised, and accessible as the layer 1, it poses new risks for the users of the system. For this reason, we do not believe that layer 2 technologies are a future-proof solution to this problem.

This implies that all previous efforts to make a decentralised system scalable (whether layer 1 or layer 2 solutions) have had to cut back on either security and/or decentralisation.

However, Bitcoin is a great example of the importance of decentralisation and security in a money system. Every serious bitcoiner (some call them Bitcoin maximalists) understands that there is no other cryptocurrency that is as decentralised and secure as Bitcoin, which are the two most critical features of a future-proof money system.

In addition, features such as censorship-resistance, stability, permissionlessness, neutrality, incorruptibility, etc. are essential for the success of a DLT-based solution. Because of all these characteristics, it is virtually impossible for powerful (groups of) individuals, organisations, governments, companies, billionaires, etc. to exert significant power over Bitcoin. Because of these characteristics, nearly 14 years after its release, Bitcoin remains the most valued decentralised digital money system, despite its flaws.

So imagine where we could be right now if Bitcoin possessed each of the following characteristics:

| Bitcoin | Desired money system | |

|---|---|---|

| Scala-bility | Between 2 and 6 transactions per second in the past 7 years | At least ≈ 43,000 transactions per second to be able to compete with the current digital fiat transaction volume (and even more in the coming years); Ideally no limit |

| Speed | On average at least 5 minutes (with a blocktime of 10 minutes) | Under 5 seconds for most (>90%) transactions (10 seconds maximum) |

| Finality | Between 1 and 16 hours | Immediately (only depending on the speed of the transaction) |

| Fees | The daily median transaction fee has been between a few cents and US$34 in the past 7 years | No transaction fees cause spam and aren’t economically viable for a DLT system; however, fees should be predictable and no more than 0.1% of the transaction amount (with a hard upper and lower limit) |

| Energy usage | 2,188.59 kWh / transaction (as of April 25, 2022) [total energy consumption of the Bitcoin network is still less than the banking system] | The absolute bare minimum (only what is necessary for the verification and processing of transactions) |

| Privacy | Bad by default, but tech-savvy people can improve it | Medium privacy by default and strong privacy on demand (similar to Litecoin’s MWEB) |

We are firmly convinced that the global adoption of Bitcoin is much slower than it could be due to its lack of these cash-like characteristics and its poor user experience, and that this is why so many companies have ceased accepting Bitcoin as a payment method.

Therefore, in order for a digital money system to be a viable alternative to the fiat monetary system, it must not only be able to withstand all influences from governments, organisations, companies, etc. but also meet all the requirements of a future-proof money system.

So, what exactly are the requirements for a future-proof money system?

Requirements for a future-proof money system

A future-proof money system must first and foremost fulfil the three functions of money (as described in the earlier section What is a trustless money system?):

Critics of digital money (such as Peter Schiff) like to argue that cryptocurrencies fail as both money and a store of value because they lack utility and intrinsic value. Only if they’re backed by something that has either of these properties can they be used as a digital representation of their underlying value. Apart from the fact that ‘intrinsic value’ is not a well-defined term, intrinsic value is not even necessary for a pure monetary good.

Just look at the intrinsic value and real world use case of seashells, wood sticks and paper. Obviously, their values are relatively small, yet despite this they have been used as money in the past. Even gold, if we omit its monetary utility, has a demand in the industrial sector of just over 8%. This indicates that the vast majority of gold’s value does not stem from being a noble metal, but rather from its use as a monetary good. Therefore the majority of gold’s value is ultimately a social construction. Gold is valuable because people agree it has been and will be in the future. And why do people agree on that? Because it’s scarce.

As Satoshi accurately hypothesised, a pure monetary good does not require any attributes other than the assurance of being scarce and easily transactable. Over the past decade, the crypto market has confirmed this notion to be true. Therefore, a pure monetary good is subject to different laws than traditional goods and services in a free market economy.

But what else are the requirements for a future-proof money system?

In addition to the three functions of money, a future-proof money system must possess the following basic characteristics:

- digital / intangible (not physical / tangible)

- easy to store (self-custodiability)

- easy to identify (recognizability)

- easy to divide (divisibility)

- easy to transport (portability)

- easy to transact remotely (remote-transactability)

- scarce / limited / fixed in supply (not inflationary)

- non-replicable / unforgeable (not like common digital files)

- fungible / anonymous (no distinction between coins to guarantee anonymity; or at least optional privacy for users, as is the case with fiat currencies (e.g. credit card / bank wire vs. cash))

- transparent / open source (not obscure processes and decision-making)

- fault tolerant / stable (no single point of failure)

- global / borderless (not just regional like fiat currencies)

- censorship-resistant (not possible to ban or censor specific users or groups)

- neutral / apolitical (not highly politicised as fiat currencies)

- durable / immortal (not like fiat currencies that come, collapse and go)

- incorruptible / indestructible (no possibility to take over the system with money or power/authority)

- decentralised (not controllable by a single person or small group of people)

- permissionless (no restriction on who can participate in the operation)

The most crucial aspect is that these characteristics do not change, i.e. that there will never be a monetary policy reform in the DLT system. Under absolutely no circumstances!